Section 1 of 4: Description of Setting

The professional settings in which I served as an in-school mentor and as a literacy and mathematics tutor was in three different public elementary schools in the southern Ontario, Canada, in the region of Peel. One of my students was in grade eight in a middle school in Brampton, Ontario, northwest of Toronto. Another student, whom I tutor mathematics, was in grade three at an elementary school in Mississauga, Ontario, west of Toronto. Nine of my students, to whom I was a literacy tutor, were in an elementary school in Brampton, Ontario, northwest of Toronto. Most of my work related to classroom management was conducted in the two elementary schools.

In the elementary school in Mississauga, ten children from a variety of elementary grade levels entered their school’s library quietly at the beginning of the fifty-minute lunch period once per week, which helped them practice respectful social behaviour. They took a seat at the table where their tutor was sitting. They began eating their lunch while their tutor, such as me, engaged them in conversation about how their week went both outside of school as well as during school. Questions tutors ask their students included what the best part of their week was with follow-up questions to engage the child in dialogue. This procedure helps children feel welcome and of value since the conversation’s focus was on them, their feelings, and on their experiences.

Once the children are finished lunch, they tidied up by putting their recyclable materials into the designated recycle bin near the doorway entrance to the library, and their reusable containers back into their eco-friendly lunch bags. Again, this procedure reinforced positive, respectful social behaviour and environmental stewardship. This is where established rules and procedures of each tutor differed. My peers followed the mathematics workbook page by page and unit by unit. This procedure fails to take into consideration whether a student has mastered any portion of a unit or if the underlying skills necessary to learn a particular unit are under-developed.

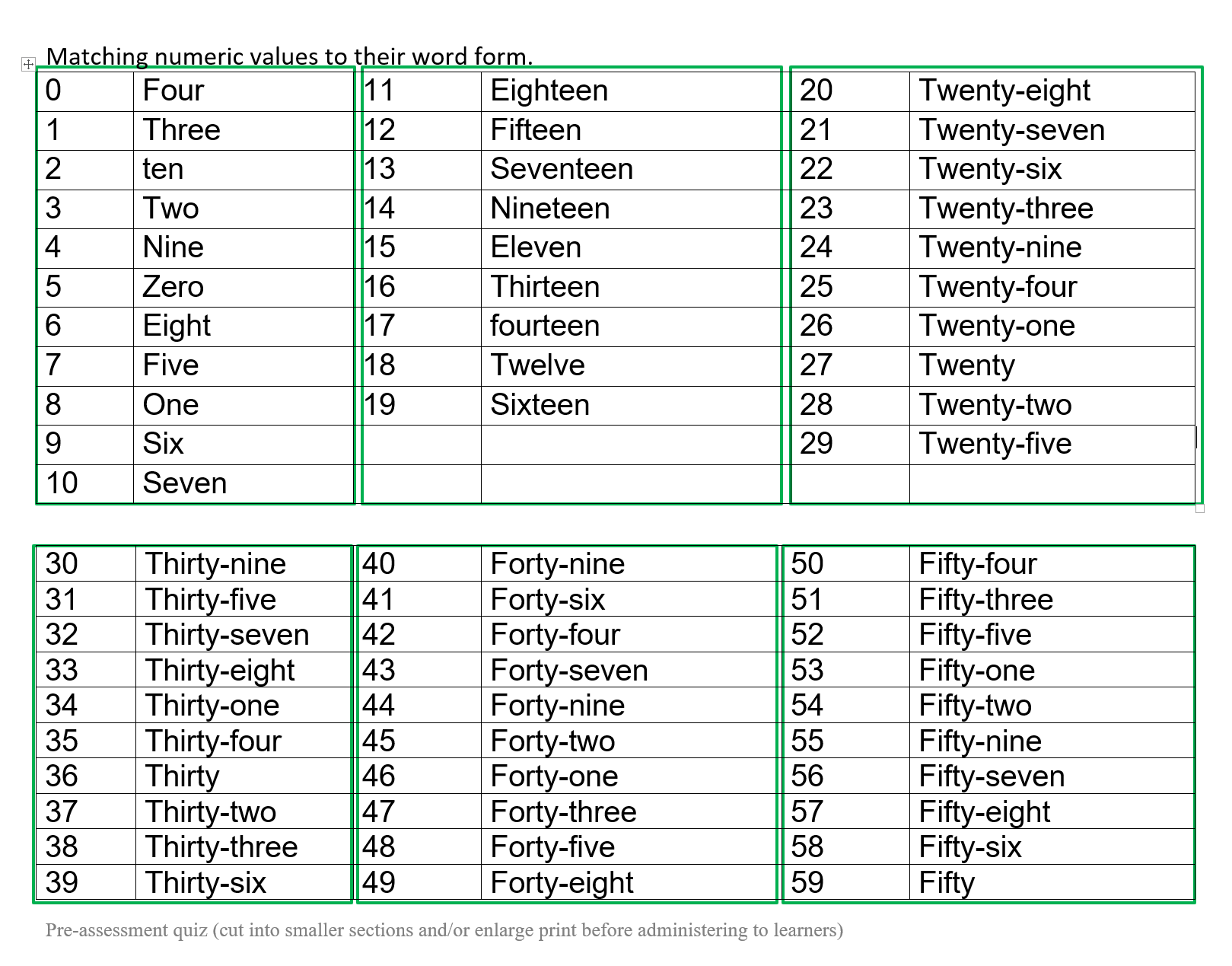

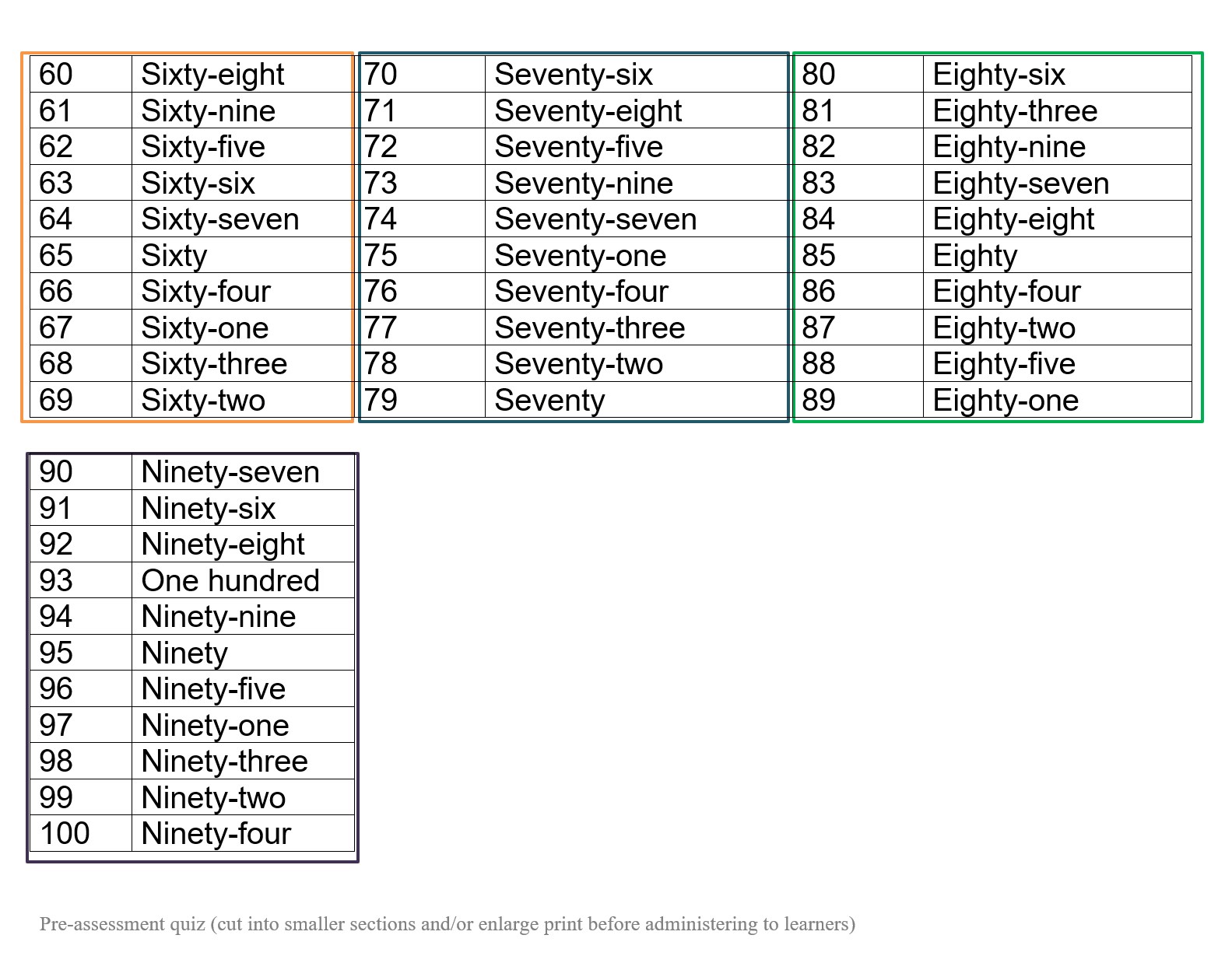

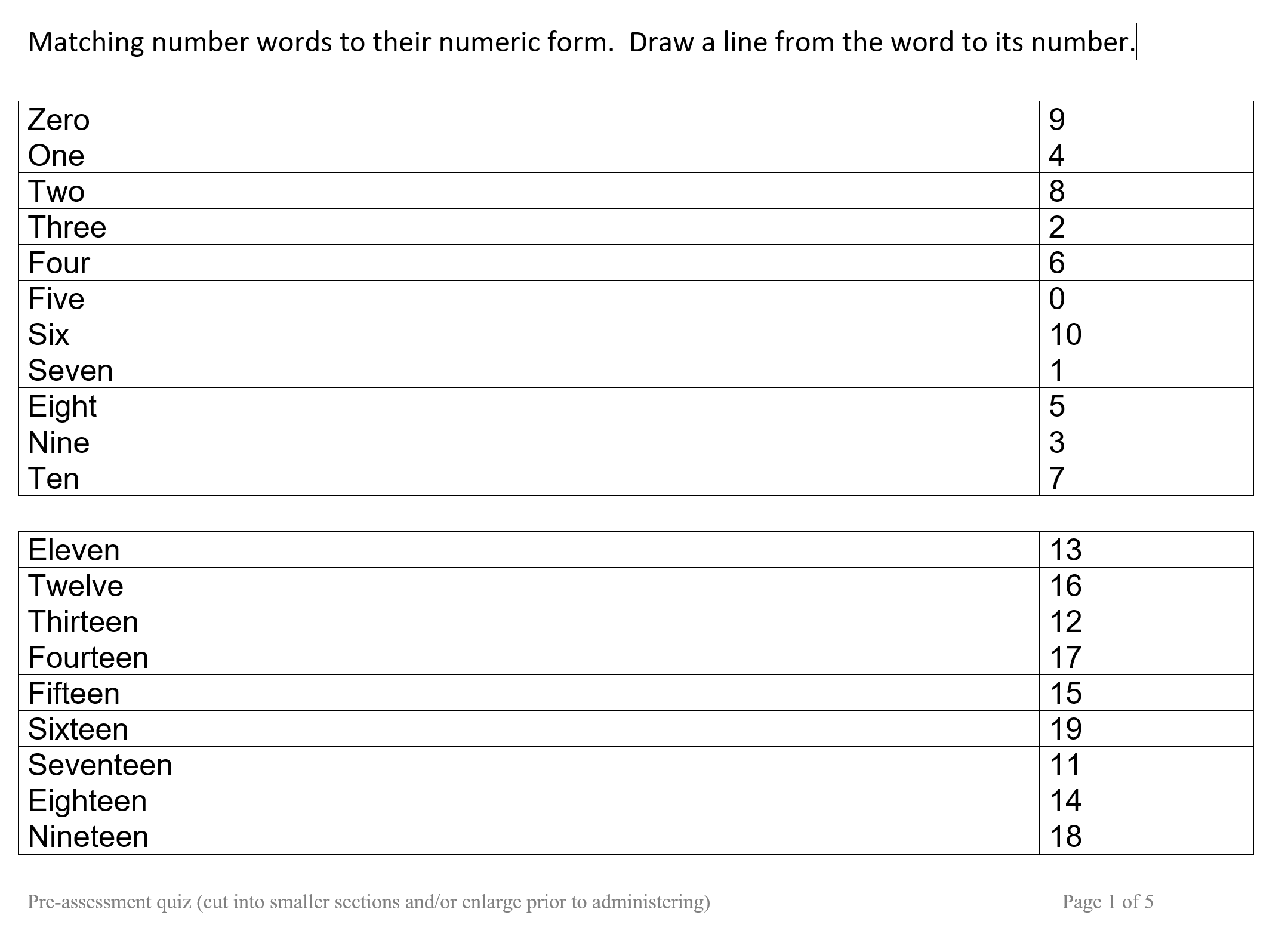

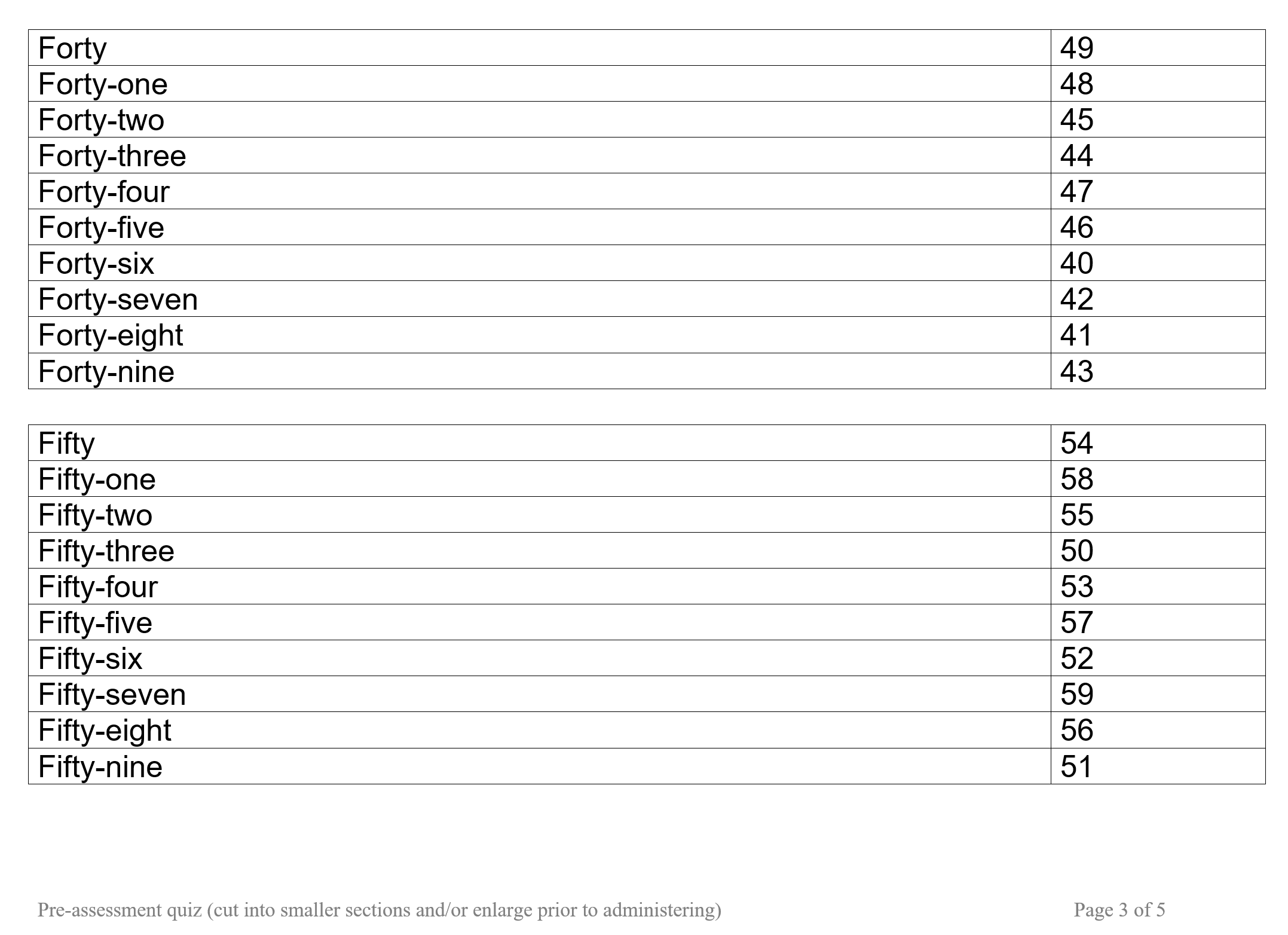

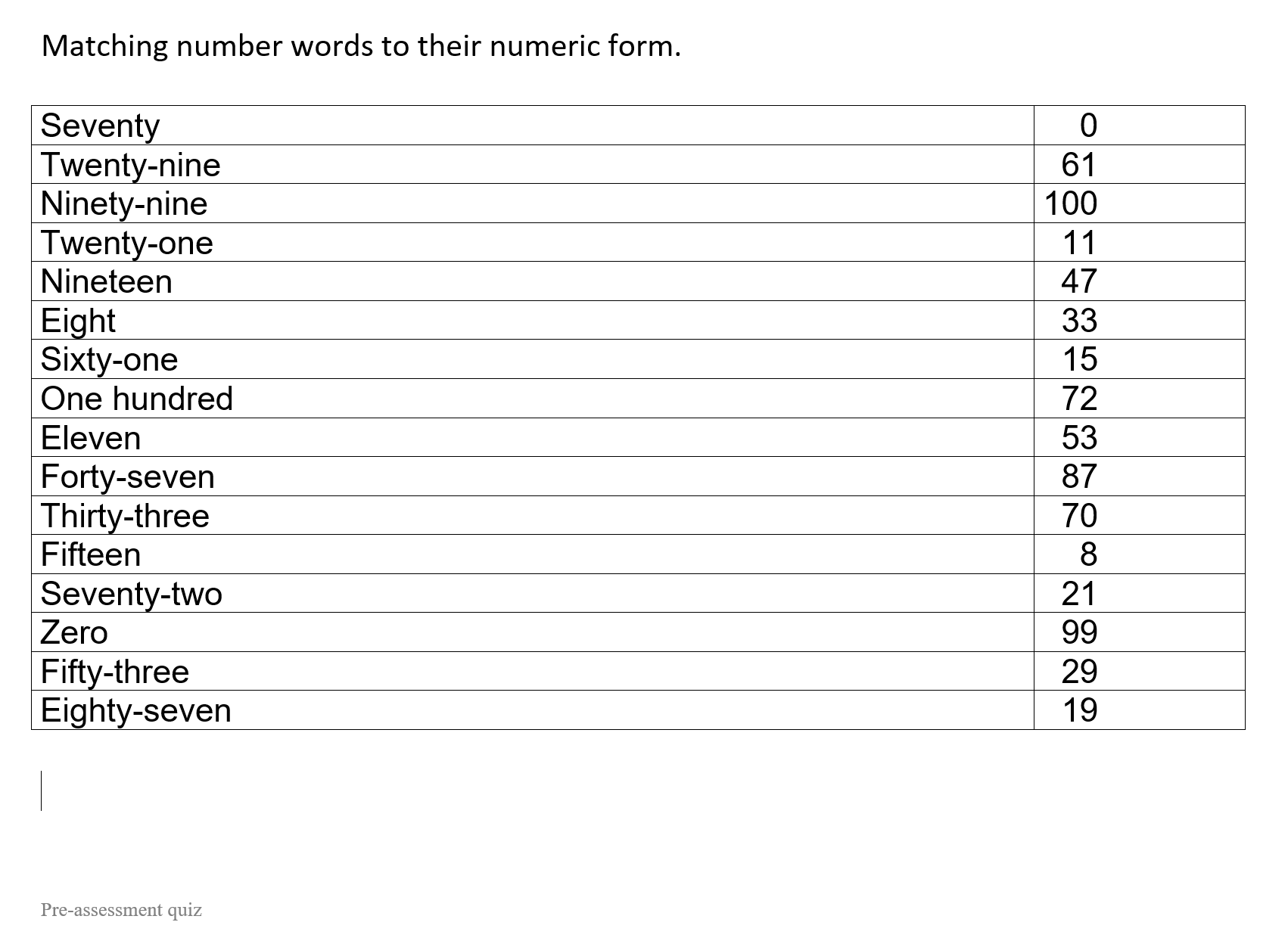

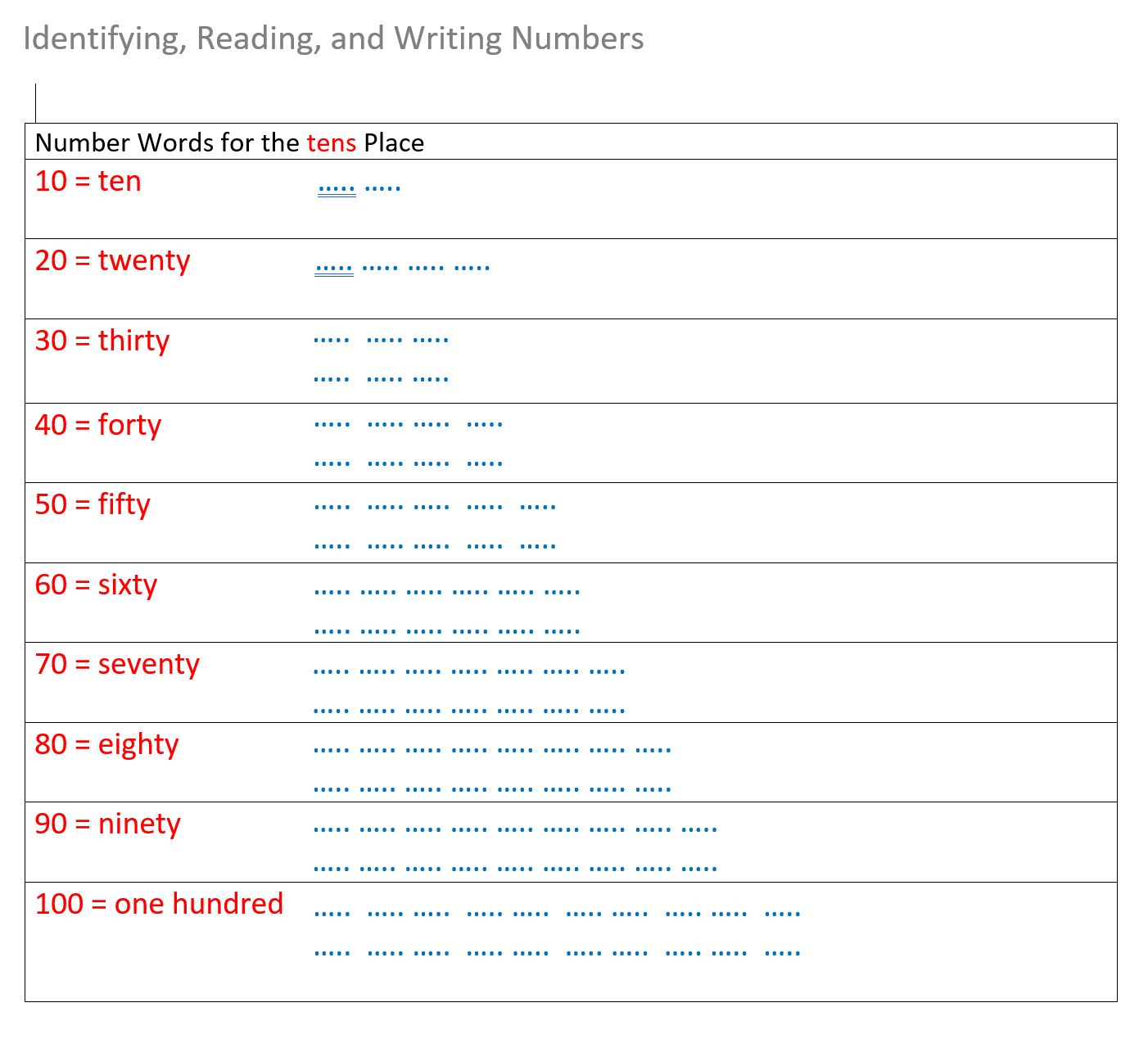

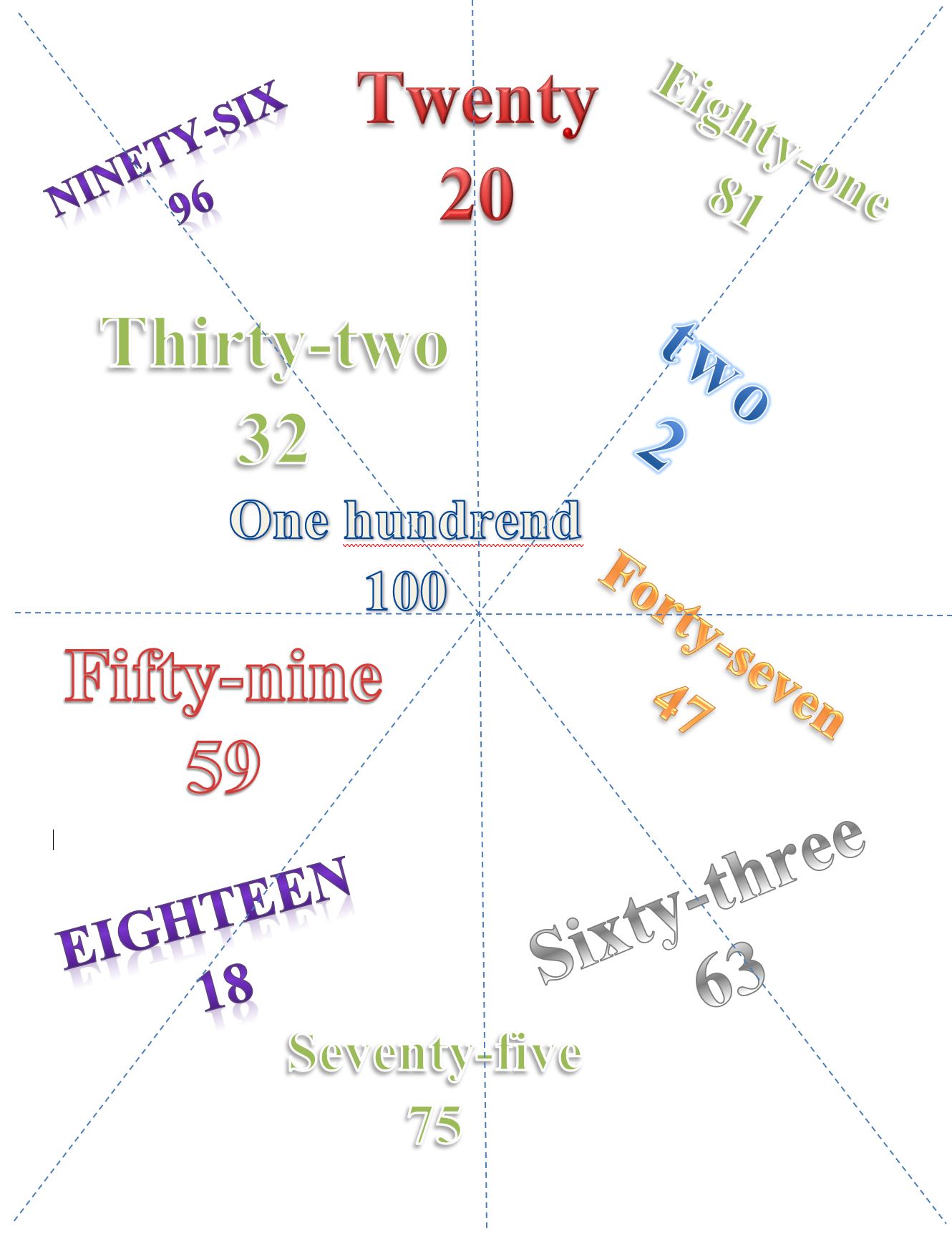

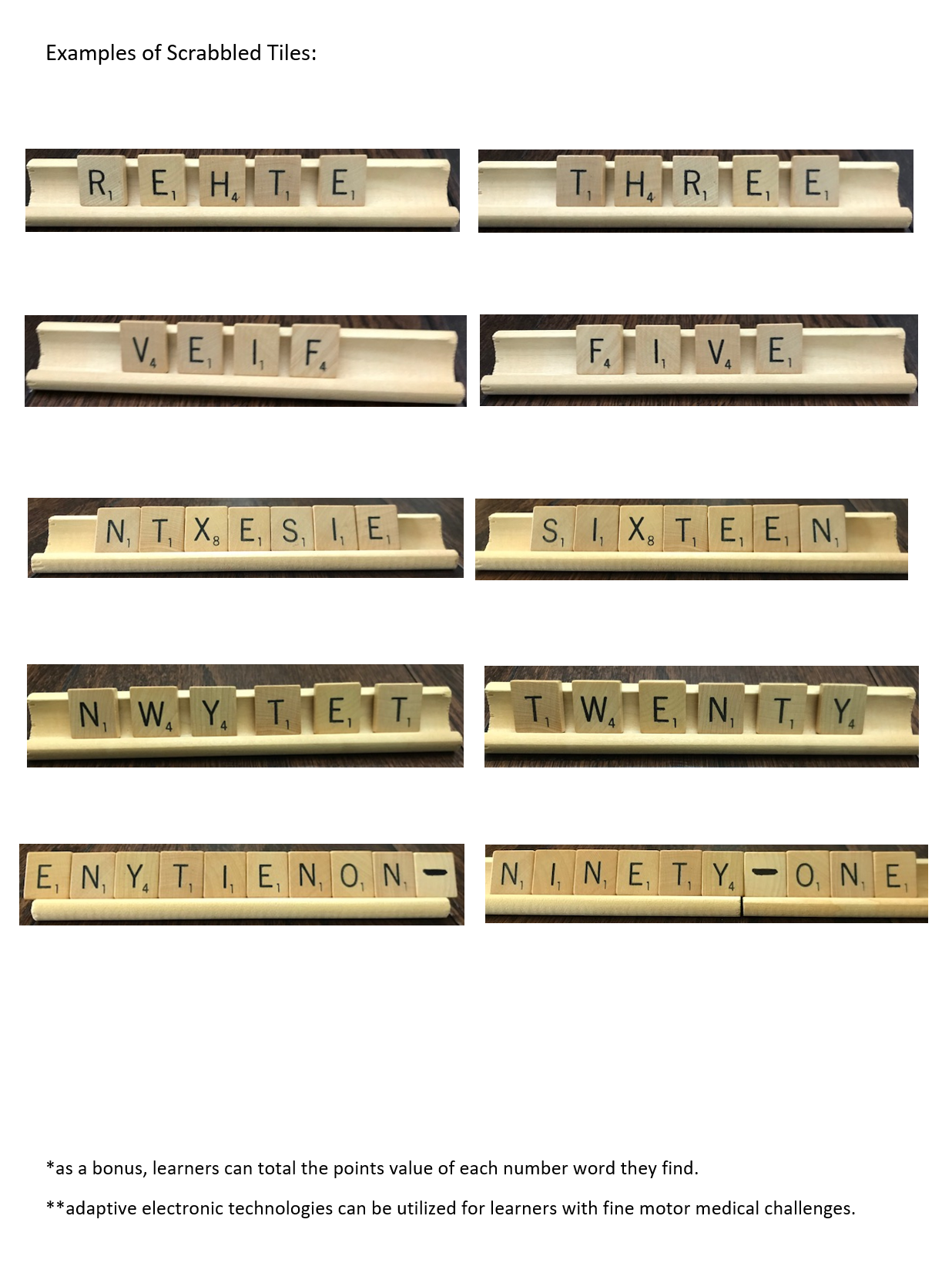

Unlike my peer tutors, I asked my student what mathematics topics they are currently learning about in their class. Then, to uncover the student’s extent of comfort and understanding of the mathematics topic, I provided a student-friendly and fun informal assessment for completion by the child (Jones & Jones, 2010; Marzano, Marzano, & Pickering, 2003). If their understanding was high, greater than ninety percent, I gave the child the opportunity to choose which mathematics topic they wanted to learn more about during the thirty-minute tutoring session, once they had eaten lunch. If the student’s knowledge and understand of a unit’s topic required the development of deeper understanding, I linked the unit’s workbook exercises to their own experiences and learning preferences such as drawing objects, using imitation coins and play paper money, number lines, a hundred board, finger counting, and using graph paper. Thus, this seatwork provided the student with “meaningful practice while enabling [the student and I] to assess the student’s progress” (Jones & Jones, 2010, p. 208). To the greatest extent possible, I involved my student in the formation of the rules and procedures according to the child’s specific needs, processing, and learning styles. Thus, creating a learning environment with “structure and security” (Jones & Jones, 2010, p. 216).

In the Brampton elementary school where I was a literacy tutor to nine students below grade level reading skills, I moved a child sized desk and two chairs into the hallway just outside the entrance to the kindergarten classroom. I moved three adult sized chairs into the hallway as well. Upon two of these chairs, I arranged randomly yet neatly, recovery readers’ levels one and two of a variety of interest stories. The special education teacher provided me with a notebook into which I recorded the student’s name, the book they chose to read, the book’s level, the words I prompted them to read; words they mispronounced; words they mis-decoded, their favourite sentence, as well as their description of the book’s theme. The students would print the last two items (their favorite sentence and description of the book’s theme), cut out the words, and then re-assemble the words in sequence onto a graphic organizer that I designed for them. I worked with students for twenty-minute segments of time, once or twice per week, one-on-one or in pairs depending on a learner’s preference. Once the reading and cooperative behavior goals were achieved, the students had an opportunity to read a high interest book of their choice, draw a picture, and/or choose a sticker.

Once my mathematics student reached a level of mental fatigue, when the learning process is no longer fun (this is easily observed in facial expressions and body language), I asked the student to choose from among several mathematics-based board and other games such as “Four in a Row”, “Snakes and Ladders”, “Cards”, “Sorry”, etc. which they got from a designated storage area (Marzano et al, 2003). I adapted board games so that the players must determine the product of the two-die rolled. The player then moved their game piece that many spaces; thus, making use of adding and multiplication mental-math skills when playing “Snakes and Ladders”. When the lunch bell rang, all the children tidied up and put the games they were playing away in the designated storage area. In the elementary school where I was a literacy tutor, students expressed their mental fatigue, stress from too much cognitive challenge, or boredom using disruptive or unproductive behaviors.

My greatest challenge involving classroom management was my first practical experience teaching a class of twenty students when I did my final practicum course necessary to earn the Master of Science in Education degree in 2012.

Section 2 of 4: Data Collection

Classroom Management and Student Learning

Upon reflecting about how closely I attended to the types of procedures discussed by Jones & Jones (2010) and Marzano, Marzano, & Pickering (2003), specifically regarding my methods of developing, establishing, and consistently implementing rules and procedures, I would self-rate as 80%. There was definitely room for improvement. I definitely ensured that no more than three clearly stated behavior expectations, or rules, were co-developed by the student and I, through brainstorming what they need in order to feel safe, trusting, and trusted (Jones & Jones, 2010; Marzano et al, 2003). The three rules of conduct were listening kindly to others, showing gratitude by complimenting others and never giving insults, and showing respect mutually regardless of race, gender, age, learning ability, culture, city or country of origin, socio-economic status, family structure, body type, or other physical or intellectual differences (Gibbs, 2001). This latter rule of conduct also applied to personal property and privacy rights. My shortcoming though was that the student had not the time to internalize the behavior expectations with the reasons for each of them.

Therefore, I asked the student to create for themselves a reference card that outlined the behavior expectations and why these rules were formulated. However, I did discuss the behavior expectations frequently when they were first developed, the student committed to following them with a clear understanding of the consequences for violations, which would be the removal of the privilege to play a game near the end of tutoring session (Jones & Jones, 2010). Furthermore, this implementation acknowledges my belief that teaching children that there are consequences to unproductive and/or harmful behavior prepares them for life in the world of societal reality. In the future, I asked students to print the rules in their own journal booklets and/or act out the rules as this would serve to enhance cognition through the use of motor skills and/or physical activity, respectively (Silver, Adelman, & Price, 2003).

The procedures taught to the student governing the tutoring session included taking into consideration whether they had mastered any portion of a unit or if the underlying skills necessary to learn a particular unit were under-developed. Unlike my peer tutors, I asked my student what mathematics topics they were currently learning about in their class. Then, to uncover the student’s extent of comfort and understanding of the mathematics topic, I provided a student-friendly and fun informal assessment for completion by the child (Jones & Jones, 2010; Marzano, Marzano, & Pickering, 2003). If their understanding was high, greater than ninety percent, I give the child the opportunity to choose which mathematics topic they want to learn more about during the forty-five-minute tutoring session. If the student’s knowledge and understand of a unit’s topic required the development of deeper understanding, I linked the unit’s workbook exercises to their own experiences and learning preferences such as drawing objects, using imitation coins and play paper money, number lines, a hundred board, finger counting, and using graph paper. Thus, this seatwork provided the student with “meaningful practice while enabling [the student and me] to assess the student’s progress” (Jones & Jones, 2010, p. 208). If the student failed to follow the procedure, I immediately retaught that procedure and, using cognitive coaching methods, ensured the student understands why that procedure is in place (Costa & Garmston, 2002; Marzano et al, 2003).

In other areas in which I needed improvement regarding the rules and procedures that applied to the tutoring session were that the student’s parents did not know the rules and procedures, nor did they “know my methods of handling discipline problems” (Jones & Jones, 2010, p. 218). My strategy to change this for the next school year was to send home with the student a list of the behavior expectations and the tutoring session procedures in English and the first language spoken at the student’s home. In addition, I would request parents/guardians to read the list with their child; then sign and return the form to me, as I understand how important parent involvement is, particularly if they agree to collaborate by enacting school and classroom rules at home as well as when they are out in the community with their children.

In addition, once I had a primary elementary classroom to teach, I implemented the use of the “Yacker Tracker” to monitor classroom noise levels (Jones & Jones, 2010, p. 192; Inspiring Teachers, 2011). Furthermore, I planned to use the finger puppet technique described by Jones & Jones (2010) on page 192 in their Developing Standards for Classroom Behavior to help young children remember procedures and behavior expectations. Another promising strategy to teach and reinforce classroom behavior expectations and procedures would be to let students choose a project based on their individual interests, learning styles and strengths from a modified list based on a such a list in the Jones & Jones’ (2010) text’s figure 6.8 on page 190.

References

Costa, A.L. and Garmston, R.J. (2002). Cognitive Coaching: A Foundation for Renaissance Schools (2nd Edition). Norwood, Massachusetts: Christopher-Gordon Publishers, Inc.

Gibbs, J. (2001). Tribes, A New Way of Learning and Being Together. Center Source, Windsor: California.

Inspiring Teachers (2011). Yacker Tracker Deluxe, Retrieved on April 14, 2011 from http://www.inspiringteachers.com/catalog/supplies/deluxe.html

Jones, V., & Jones, L. (2010). Comprehensive classroom management: Creating communities of support and solving problems (9th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Allyn & Bacon. ISBN: 9780205625482.

Marzano, R. J., Marzano, J. S., & Pickering, D. J. (2003). Classroom management that works: Research based strategies for every teacher. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. ISBN: 9780871207937.

Silver, M., Adelman, B., and Price, E. (2003). Total Physical Response: A Curriculum for Adults. Retrieved on May 20, 2011 from http://www.springinstitute.org/Files/tpr4.pdf

Understanding Unproductive Behavior

I found the case study depicted in the Jones & Jones (2010, p. 193) text entitled, “Dealing with the Dilemma of Gum Chewing”, an excellent representation of the use of a positive behavior strategy focused on the teaching of the procedure of gum chewing rather than on enforcing rules and implementing punitive measures. Treating children with dignity and respect means focusing on helping them “to develop good character and become accountable for their behavior” …”as student-citizens capable of learning personal responsibility” (Jones & Jones, 2010, p. 193).

I encountered a similar situation in an educational setting where a positive behavior strategy such as the one portrayed in the gum chewing case study would have yielded more productive results than what I had implemented. The situation involved several students who continuously forgot to tidy up their desks after eating their lunch, including placing recyclable materials into the bins provided, and would rush out the door for recess. In hindsight, rather than just reducing their recess time the following day, the positive behavior strategy of teaching the procedure of how to tidy up after lunch, and providing reinforcing praise and perhaps even stickers, or extra computer time for example, for doing so over four or five consecutive days, would have strengthened their own autonomy.

Jones & Jones (2010, p. 44) state, “research…indicates that students are more likely to engage in positive behaviors and refrain from high-risk behaviors when they experience opportunities to develop positive personal assets”. One of those assets is the support of a caring, safe, and encouraging school climate where parents/guardians and other family members are actively involved in helping children succeed in school. A preliminary part of creating a caring, encouraging, safe, and supportive school climate is the teaching of appropriate expected behaviors. When children feel safe at school, they are empowered to learn through exploration, which is another positive personal asset. Furthermore, when children know and understand the boundaries, consequences, behavioural expectations, and have constructive extra-curricular programming in which to engage, they are encouraged to do well. Moreover, teaching appropriate expected behaviors using positive behavior strategies to children increases the likelihood that their bond with the school, achievement motivation, school engagement, and overall commitment to learning will improve (Jones & Jones, 2010). As well, positive values, social competencies, and a positive identify are more likely to develop when the teaching of the appropriate expected behaviors supports established behavior expectations. Therefore, the ethical issues involved in establishing expectations without teaching the appropriate expected behaviors are that children’s autonomy and esteem are left floundering, resulting in a greater likelihood that negative, unproductive, disruptive, hurtful, and high-risk behaviors will proliferate in classrooms and the school environment as a whole.

References

Jones, V., & Jones, L. (2010). Comprehensive classroom management: Creating communities of support and solving problems (9th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Allyn & Bacon. ISBN: 9780205625482.

Inclusion and Motivation

The mini-intervention I planned and implemented for the third-grade student whom I tutored mathematics went well. The student was very responsive to all phases of the intervention from my initial giving of appreciations for the student’s accomplishments and positive attitude through to our verbal agreement to play a word game of the student’s choice while walking at a calm pace together to their classroom after every tutoring session, sealing it with a handshake. What seemed to interest the student the most was watching the YouTube video entitled Hallway Safety, which was the collaborative effort of several high school students from Central Dauphin High School located in Harrisburg, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania in the United States (CDHS, 2010). The dialogue about why there are rules was of less interest to the student based on the diminished enthusiasm the student expressed facially (their broad smile relaxed to a grin) and observed body language (their upright, forward leaning posture relaxed). The drawing of mind maps was a challenging task for the student, but well appreciated by the student when they reviewed their finished product. Therefore, the use of mind mapping was a worthwhile positive experience and quite useful at encouraging the student’s critical-thinking and problem-solving skills. Overall, the intervention had been successful since the student had been exhibiting the appropriate expected behavior of walking with me to their classroom at the end of the tutoring. There have not been any surprises since the mini-intervention was implemented.

In a way, the mini-intervention was a mini class meeting between two participants who were the student, and I. One article I reviewed by Edwards & Mullis (2003, p. 20) presented research-based findings from numerous studies that asserted classroom meetings “serve as an excellent vehicle for teaching” … ”students the academic, social, and emotional skills they must possess to function successfully at home, at school, and in the community”. Furthermore, according to this same article, “A substantial body of research implied that explicit instruction in social problem solving, especially those that teach empathy skills, averts subsequent problem behavior” Edwards & Mullis (2003, p. 20). Research also attests to class meetings helping students generalize conflict resolution instruction to real life situations because they are afforded practice of the necessary skills in a safe, controlled environment. I am confident the mini-intervention I implemented provided the student with exactly these life skills lessons. Upon closer examination, the mini-intervention generally followed the agenda structure outlined in the Edwards & Mullis article: I began with appreciations and compliments, followed by a peaceful conflict resolution and problem-solving activity using mind mapping and showing the YouTube video. Then, we practiced a little more problem-solving specific to the Hallway Safety video. However, the mini-intervention did not include what would be considered as old business or new business. Yet, the word game we played on the way back to the student’s classroom would be considered a “classroom encouragement activity”, according to Edwards & Mullis’ (2003, p. 23) description. Based on the positive outcome observed regarding student appropriate expected behavior, I would use the Edwards & Mullis (2003) structure of a class meeting for all future teaching situations, both professionally and in my personal life.

References

Edwards, D., & Mullis, F. (2003). Classroom Meetings: Encouraging a Climate of Cooperation. Professional School Counseling, 7(1), 20-28. Retrieved from EBSCOhost .

CDHS (2010). Central Dauphin High School Hallway Safety, uploaded on Feb 5, 2010. Retrieved on April 10, 2011, from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ue0TElhHy0Y

Teaching Productive Behavior

I was fortunate to have opportunities to exercise my spontaneity and flexibility. When one of the tutors was away, a third-grade student, who is from the same classroom as my student, was without a mathematics tutor. My student and I invited that student to join us for the lesson Remainders, which my student selected from among several choices about division. Offering my student a choice of how they wanted to learn about division was one way I adjust my teaching style to meet the needs of my learner. Providing flexible learning goals by “asking [the student] what they would like to learn conveys a sense of cooperation”, and “has the potential to increase [the student’s] interest in the topic” (Marzano, 2003, p. 52). In addition, it also conveys the message that I am concerned about their interests and that I am attempting to include those interests in my instruction (Jones & Jones, 2010). The guest student also made a choice to participate in the lesson about Remainders.

Then, I moved my chair, positioning it between the two students and slightly behind so as not to interfere with peer joint attention and co-learning, thus adjusting my teaching style to encourage collaboration between the students, yet I was close enough to provide scaffolded support as needed. I used visual representation as a formative instructional and assessment method to check for student understanding. This consisted of the students drawing a predetermined number of two-centimetre diameter circles to represent plates (the students’ imagery choice, one for each make-believe number of guests) on which a certain number of dots (the students chose to pretend the dots were cookies) would be placed to fairly distribute the make-believe cookies. I modeled two different scenarios for the students. Then, they were given six problems to solve individually on paper but were permitted to check with each other for help if they wanted to do so.

One example, the students were asked to problem-solve was the distribution of nine dots (again, they pretended the dots were cookies) among four guests (i.e., circles drawn to represent plates). Each student looked at the other, brainstormed what to do, each drawing on their own papers four circles to represent the plates. Then, they drew nine dots, representing cookies, in a rectangle, that represented a container. The students were asked to distribute the cookies fairly among the four guests (i.e., circles drawn to represent plates). As they drew a dot on each of the four plates, they crossed off one dot in the rectangle. This represented that a cookie was placed on a guest’s plate. The students used trial and error (e.g., putting three cookies on one plate and two on each of the other three). I used a formative questioning technique to extend their problem-solving skills asking, “Is that fair? Does each of your guests have the same number of cookies? What can you do to make it fair?” and a reminder, “Remember, it’s OK to leave some cookies in the container (i.e., the rectangle).” The students learned to make it a fair distribution through the process of adjusting the number of dots they had drawn in each circle (i.e., guest’s plate).

Each student then filled in the blanks for the following statements: ___ dots (i.e., cookies) in each circle (i.e., on each plate); ___ remaining. This progressed to the students writing a mathematical division statement for their pictures such as 9 ÷ 4 = 2 R1 (where R represents remainder). I then used formative follow-up probes such as “Please explain why you distributed the cookies this way”.

What I learned from this tutoring session is that the students may have found it more beneficial to use manipulatives, that is, concrete items to distribute among drawn circles to represent plates or use actual containers. Therefore, for the next week’s tutoring session included forming their own division problems for the other to solve and writing a mathematical division statement, but they used tokens or marbles to distribute among small Dixie cups; or colourful small magnets on a small magnetic dry-erasable white board, which would combine both drawing and manipulatives. All of these are ways in which I adjusted my teaching style to meet the needs of my students.

Instructors who do not make accommodations or modifications to their lesson plans, instruction, and assessments are expressing the message that those students who do not learn or process information the same way as the teacher do not belong in their classroom, and even worse, is not worthy or considered valued by that teacher. This bias and prejudiced attitude is harmful to children’s self-efficacy. It also sends the wrong message to other students in the classroom that it is “OK” to devalue others based on learning styles differences. It is also evidence of someone in a position of trust and power who is either untrained in the implementation of developmentally appropriate practices or they have an intellectual superiority complex. Moreover, such behavior on the part of an educator could be viewed as neglectful and negligent non-demonstrative care of children. This is where instructional equity becomes visible as a classroom challenge that only debilitates children with learning differences overall development.

What magnifies this problem is the level of teacher unpreparedness regarding differentiation of instruction, assessment, and utilizing various strategies and techniques known to reduce or extinguish unproductive behaviors. Even worse, are situations where teachers attend, or choose not to attend, professional development that address gaps in sound educational practice. In addition, there are teachers who do not implement the knowledge and skills taught during professional development sessions. For the students these effect, these are hugely unacceptable realities, as they should also be for those in powerful positions in government.

References

Jones, V., & Jones, L. (2010). Comprehensive classroom management: Creating communities of support and solving problems (9th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Allyn & Bacon. ISBN: 9780205625482.

Marzano, R. J., Marzano, J. S., & Pickering, D. J. (2003). Classroom management that works: Research based strategies for every teacher. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. ISBN: 9780871207937.

Teacher Behaviors and Classroom Management

As a means to improve my teaching skills, I tracked the ways I responded to learners performing at different levels during the literacy tutoring I engagde in with nine kindergarten students for two and a half hours in the morning at a public elementary school once per week. When I reflect on the surprises, I have to admit that the extreme difference between the higher-achieving students and the lower-achieving students did leave me feeling a bit helpless at first. There was a considerable reading and printing skill gap between the higher- and lower-achieving students. However, I quickly overcame my feelings of astonishment and focused my efforts not just on finding structured supportive ways to assist the lower-achieving students, but also on implementing strong encouragement for the higher-achieving students to provide constructive support to their lower-achieving peers mostly in the form of modeled reading while sharing the same book of interest. This latter method seemed to be the most productive overall as the lower-achieving students began following the lead of the higher-achieving students during word identification and pronunciation as well as constructing sentences that described the theme of the book they read together. Villa & Thousand (2005, p. 131) state that, “The ultimate goal in providing personal supports is to fade adult and formalized supports while developing natural supports that are generically available in a classroom”. Furthermore, they assert how important a role educators have regarding connecting “students and to facilitate natural support giving and receiving at every opportunity” (Villa & Thousand, 2005). In addition, the peer tutor was a terrific instructional strategy because it enabled the students “to learn and work in [an environment] where their individual strengths [were] recognized and individual needs [were] addressed”.

I learned that generally my practices are developmentally appropriate to the individual student with whom I instructed. I differentiated activities based on each child’s own developmental level. For example, providing for some student-directed activities, I asked the students to print their favourite sentence in a color of their choice from the book they mutually agreed to read, cut out the words, and then paste the words in their correct order onto a graphic organizer (Sornson, 2005). If the student was struggling with forming the letters of each word, I asked them if they would like me to print the sentence for them in pencil and then they could trace each letter of every word. The struggling students agreed to do this. If the students had difficulty cutting out the words, I drew thick lined boxes around each word and asked them to cut along the lines I drew. The students viewed this as constructive support and not as demoralizing most likely due to my tone of voice and the words I chose to use to ask their permission to help them. If a student had difficulty re-assembling the words into a sentence, I gave them the book they read to use as a guide as they pasted the words in their correct order onto a graphic organizer.

I used the same constructive, structured, and supportive techniques when I asked the students to print a description of the main idea of the book they read, this time pasted onto a graphic organizer of their choice, also a student-directed activity (Sornson, 2005). Providing the students with choices is a sound instructional and management strategy. Researchers, such as Jones & Jones (2010, p. 308), attest to this stating, “[choices respond] to students’ need for competence and power and helps to reduce their perception that someone is trying to control them or is going to do something to them”, thus, increasing their perceptions of their own efficacy. Though my attention was shifted from the higher-achieving students to the lower-achieving students initially, once I began encouraging the paired students to read collaboratively, my attention was more equally divided among them as the higher-achieving students began providing natural support to their peer partner.

References

Jones, V., & Jones, L. (2010). Comprehensive classroom management: Creating communities of support and solving problems (9th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Allyn & Bacon. ISBN: 9780205625482.

Sornson, B. (2005). Creating classrooms where teachers love to teach and students love to learn. Golden, CO: The Love and Logic Institute. ISBN: 9781930429871.

Villa, R. A., & Thousand, J. S. (2005). Creating an inclusive school. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. ISBN: 9781416600497.

Changing Individual Behavior

I reflected on the literacy tutoring I engaged in for nine kindergarten children in a public elementary school, as identified by the classroom teacher and the special education teacher, as having below grade and age level reading skills. Originally, I was tutoring once per week from 9:15 a.m. until 11:15 a.m. I tutored twice per week during the same period on both days. One child in particular displayed reoccurring unproductive off-task behaviors on a regular basis, which occurred more frequently during their read aloud time. All the students I tutored chose from among several level 1 and 2 age-appropriate storybooks to read aloud. Unfortunately, I found myself redirecting this one student back to their reading aloud activity several times during our tutoring session with another peer; and even more frequently when I tutored the student one-to-one.

If I had been more aware and thorough utilizing what I know now regarding implementing a functional behavior assessment, I would have assessed and put into place an individual behavior-plan a few weeks earlier to increase the likelihood that the unproductive off-task behavior would be on its way to extinction. I would complete a comprehensive functional behavior assessment using data collection of behavior frequency. Next, I would determine the antecedents and consequences related to the student’s behavior with a thoughtful and careful analysis of these sources of evidence. This I would do to assess the function of the behavior; followed by the establishment of a variety of accommodations, modifications, and adaptations to the tutoring environment, academic work/activities, as well as the implementation of a self-efficiency skills development tool (Allen & Cowdery, 2009; Jones & Jones, 2010; The Geneva Center, 2003). Furthermore, I would have continued to collect data specific to behavior frequency to the unproductive off-task behavior to discover if any of the accommodations, modifications, and adaptations had been effective.

References

Allen, K.E. and Cowdery, G.E. (2009). The Exceptional Child, Inclusion in Early Childhood Education, Sixth Edition. Thomson Delmar Learning, Clifton Park: NY.

Geneva Center (2003). Autism Intervention Certificate Training Program. May 2003.

Jones, V., & Jones, L. (2010). Comprehensive classroom management: Creating communities of support and solving problems (9th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Allyn & Bacon. ISBN: 9780205625482.

Systemic Approaches

Research practices that utilize documentation help instructors improve management in educational settings. Documentation forms an essential part of the scientific thinking process on which sound non-bias determinations for future management strategies, as well as instructional practices, are based on thoughtful and careful analysis of data collected (Allen & LeBlanc, 2005; Costa & Garmston, 2002; Danielson, 2007; The Geneva Centre, 2003; Jones & Jones, 2010; Marzano, Marzano, & Pickering, 2003; Peterson, 2004). Examples of evidence and artifacts that would have been useful for the improvement of classroom management include, but are not limited to student surveys of interests, preferred learning modalities, strengths, and weaknesses; 2+2 feedback from colleagues and students, portfolios of management checklists and observational data collection forms, pre- and post- observation forms. In addition, other helpful documentation and artifacts include IEPs, differentiated lesson plans, family contact logs, and school and district contribution logs. One may also add to this list professional contribution and development logs, action research logs, professional development, and classroom meetings logs; functional behavior assessment forms, individual student behavior plans, and a log that itemizes questions for analyzing activity directions or an assignment created to engage students learning a new concept.

The situations I encountered where I wish I had better documentation were when I had to advocate on behalf of my daughter with autism’s inclusive and equitable education. If I had data and other artifacts, including video, based documentation providing evidence of her ability to effectively function and communicate within an inclusive environment with same age peers, her placement into a general education classroom in elementary school may have occurred two or three years earlier than it actually did. In addition, I wish I knew then what I know now about demanding such documentation from my daughter’s educators for driving the differentiation of instruction and assessment. If such documentation were available, I could have held the educators and the education system accountable for the progression of her learning via augmentative and computerized technologies, the very item listed on her IEP from the age of six as her strength, which was not utilized as a learning method until she was in grade 11. The consequences intended or unintended, of incomplete or missing documentation included misguided and bias analysis of the few existing documentation that led to faulty assessments of my daughter’s behavioural situations. Thus, as a result, inappropriate accommodations, modifications, and/or adaptations were made (or as was more often the case, not made) to the classroom environment, academic work, and/or the classroom social structure and social functioning of the students in her classroom. This ultimately created antecedents that triggered a higher rate and/or intensity of unproductive, disruptive, and/or self- or other- harming behaviors from my daughter and one or more students in her class (Jones & Jones, 2010, Marzano et al, 2003; The Geneva Center, 2003).

As for my own patterns of behavior that enhance or interfere with the effective functioning of my literacy and mathematics primary grades tutoring, I intentionally abstain from expressing negative emotions of anger, annoyance, intimidation, or making punishment-related comments. Rather, I focus on being as proactive as I can by choosing to relay positive messages of empathy that focus on relationship building. I was diligent to remain conscious about my own awareness related to my body language and gestures, the words, and phrases I use to address the students, as well as my intonation. In addition, I asked the students at the end of each learning session for their feedback about the following questions, which are a modification of the Elementary School Teacher Feedback Form located in the Jones & Jones (2010, p. 91) text: Did I listen well to you?, Did I help you enough?, Do you feel I care about you?, Did I help you feel good about learning?, Do I look happy when I teach you?, Do you enjoy the activities I ask you to do?, Have I been polite?, Have I been fair?, Did you know what I wanted you to do?, Do you understand why I asked you to do the reading activities?, Did you enjoy what I taught today?, Is there anything I could do to make our reading time more fun? I chose to ask for the students’ feedback as a means to evaluate the quality of my relationship with the students. Jones & Jones (2010) explain that:

“Before implementing any of the varied behaviors you can use to create positive teacher-student relationships, you should evaluate the current quality of your own interactions with students. This approach enables us to focus changes in areas in which students’ feedback suggests that changes may be needed in order to improve teacher-student relationships” (p. 90).

I strove to use courteous, polite, and positive encouragement in the form of praises (e.g., great pronouncing…; good effort sounding out… ) remarks to students. In addition, I gave them high-fives after they performed their activities to the best of their ability. I did not to respond to the students with anger or with the intent to intimidate. I would say to off-task students in a calm matter-of-fact manner, “Do you want to earn a sticker once the activity is finished? If you want to earn a sticker, please continue with the activity. Do you need some help? How may I help you?” I delivered this message with “sincere empathy” but with firmness to allow the student “to focus on their own choices rather than on the anger and disrespect of an adult” (Sornson, 2003, p. 87). My intent was to “indicate to [the student] that their [off-task] behavior was inappropriate”, but that I also recognized that the activity may have been a bit too difficult for them to complete independently (Marzano, Marzano, & Pickering, 2005, p. 29). The token in the form of a sticker of the students’ choice was used as recognition of the appropriate behavior of completing an assigned activity (Marzano et al, 2005).

Furthermore, my body language of leaning towards the students shows my interest in them. My hands and arms were in view, and I never crossed them, nor did I engage in self-calming or self-stimulating behaviors such as wringing my hands, playing with my hair, fingers, or an object. My gestures were smooth and gentle, non-threatening. My voice tone was calm yet expressive of the positive emotions of delight, happiness, and joy.

Overall, my behavior during the learning sessions based on data I have collected was focused on “helping students learn patterns of respectful and responsible behavior within a context of positive self-concept, belief in self, self-regulation, problem-solving, and development of planning skills” (Sornson, 2005, p. 86). According to the data I collected, my tendency was to focus my attention more on lower-achieving students and using encouraging words, phrases, and praise for effort more often than the higher-achieving students. When I focused on being as expressively positive as possible through my body language, gestures, words, phrases, and voice intonation, I was able to respond to my learners with empathy and intentionality, thus inviting relationship growth. I thoughtfully implemented natural or logical consequences for behavior, specific to students’ off- or on-task behaviors. Therefore, I was proactive in my efforts to create a caring inclusive learning environment for the students. Furthermore, I felt a stronger sense of inner satisfaction when the learning sessions were over as compared to other sessions during which my intent was not as focused on my personal behaviors.

Reflecting on the above statements, I have therefore been upholding my province of Ontario’s Ethical Standards for the Teaching Profession by demonstrating responsibility in the building of mutually respectful and trusting relationships with the students through my commitment to their continued development and learning. In addition, I have demonstrated responsibility to building trusting and mutually supportive relationship with “parents, guardians, colleagues, educational partners, other professionals, the environment, and the public” (OCT, 2011). Furthermore, I actively strive “to inspire members to reflect and uphold the honour and dignity of the teaching profession; to identify the ethical responsibilities and commitments in the teaching profession; to guide ethical decisions and actions in the teaching profession; [and as the chair of a high school council, I strove] to promote public trust and confidence in the teaching profession” (OCT, 2011). Most importantly, I sought to exercise and express through my proactive instructional planning and delivery my “compassion, acceptance, interest and insight for developing students’ potential”. By building mutual trust through fair-mindedness and integrity through on-going self-reflection, I sought to uphold “human dignity, emotional wellness” as well as “cognitive” and socio-emotional development (OCT, 2011).

References

Allen, D.W., and LeBlanc, A. C. (2005). 2+2 for Teachers. Sage Publications Inc. Books. Reproduced with permission of Sage Publications Inc. Books in the format electronic usage via Copyright Clearance Center.

Costa, A.L. and Garmston, R.J. (2002). Cognitive Coaching: A Foundation for Renaissance Schools (2nd Edition). Norwood, Massachusetts: Christopher-Gordon Publishers, Inc.

Danielson, C. (2007). Enhancing Professional Practice. A Framework for Teaching (2nd Edition). Alexandria, Virginia: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Geneva Center (2003). Autism Intervention Certificate Training Program. May 2003.

Jones, V., & Jones, L. (2010). Comprehensive classroom management: Creating communities of support and solving problems (9th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Allyn & Bacon. ISBN: 9780205625482.

Marzano, R. J., Marzano, J. S., & Pickering, D. J. (2003). Classroom management that works: Research based strategies for every teacher. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. ISBN: 9780871207937.

OCT (2011). Ontario College of Teachers. The Ethical Standards for the Teaching Profession. Retrieved on June 4, 2011 from http://www.oct.ca/standards/ethical_standards.aspx?lang=en-CA

Peterson, K. (2004, June). Research on School Teacher Evaluation. National Association of Secondary School Principals. NASSP Bulletin, 88(639), 60-79. Retrieved February 15, 2011, from ProQuest Education Journals. (Document ID: 652865641).

Final Reflection on the Use of Classroom Management Techniques

My philosophy about classroom management centers on developing a positive climate for learning where all students feel safe, welcome, encouraged, and supported to be contributing, helpful, and caring members of the school’s and their larger community. It is clearly established from the course readings that researchers argue that it is the building and sustaining of caring, trusting relationships in classrooms and school-wide environments that create learning climates in which all children can succeed academically and socio-emotionally (Marzano et al, 2003; Sornson, 2005; Jones & Jones, 2010; Villa & Thousand, 2005). This is achieved through careful and thoughtful planning of classroom management strategies and tools, combined with the skill of implementation and observation, and bolstered by close and meaningful collaboration between students’ caregivers, teacher colleagues, support staff, school board specialists such as itinerants, school psychologists, speech-language pathologists, behaviourists, etc.

However, in order for students to learn to become helpful and contributing citizens of a democracy, they must learn to be reflective, meta-cognitive, problem-solvers. They need to learn that from giving support to others, they bolster themselves, and that collaboration based on mutual respect and treating others with dignity brings success in a win-win scenario. Furthermore, students must learn that unproductive and/or hurtful behavior brings negative consequences in life, and that productive and helpful, kind, and generous behavior brings positive consequences.

Ethical dilemmas that a teacher may face when making the decision to use certain rewards and punishments as part of their management plan include negative consequences that do not logically fit the student’s off-task, unproductive, disruptive, or hurtful behavior. Other dilemmas arise from not considering the underlying purpose/reason for any particular student’s problem behavior such as home influences, pre-existing physical or developmental differences, wellness, temperament, or stressful interactions with particular peers or adults. Prevention of problem behaviors is always best by gathering as much information as possible about each student’s needs and emotional and/or sensory sensitivities from the children themselves as well as from their family members in order to plan accommodations, modifications, and adaptations to instructional delivery, activities, and the classroom environment such as lighting and the seating plan. Such planning also diminishes or eliminates cultural incongruences when selecting a particular positive or negative consequence for a child.

My final statement of my philosophy of classroom management considers all these ethical dilemmas with particular consideration for special needs learners. Generally, my classroom rules centered on developing and maintaining a caring and safe learning environment. To achieve this goal my classroom was committed to upholding mutual respect and dignity for all students, teachers, staff, and caregivers, which included teaching students how to listen attentively to others. All students had “the right to choose the extent to which they will share in a group activity” such as a whole class discussion, sporting events, etc. (Gibbs, 2001, p. 95). The giving and receiving of appreciations and showing gratitude for and to others; as well as the disallowing of hurtful and/or disrespectful actions and/or comments to and/or about others, occurred in my classroom with the use of progressive discipline and positive behavior strategies (Gibbs, 2001; Jones & Jones 2010; Marzano et al, 2003; PDSB, 2010; Sornson, 2005). Finally, students and teacher reflected and shared on the day’s learning including ideas for how the teacher can make learning more enjoyable and engaging either anonymously or during a whole group dialogue.

References

Gibbs, J. (2001). Tribes, A New Way of Learning and Being Together. Center Source, Windsor: California

Jones, V., & Jones, L. (2010). Comprehensive classroom management: Creating communities of support and solving problems (9th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Allyn & Bacon. ISBN: 9780205625482.

Marzano, R. J., Marzano, J. S., & Pickering, D. J. (2003). Classroom management that works: Research based strategies for every teacher. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. ISBN: 9780871207937.

PDSB (2010). The Peel District School Board. http://www.peel.edu.on.ca

Sornson, B. (2005). Creating classrooms where teachers love to teach and students love to learn. Golden, CO: The Love and Logic Institute. ISBN: 9781930429871.

Villa, R. A., & Thousand, J. S. (2005). Creating an inclusive school. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. ISBN: 9781416600497.

Mini-Intervention 1: Teaching Intervention Plan

Description of the Behavior

Subsequent to the conclusion of a fifty-minute mathematics tutoring session, which takes place in the library on the main floor of the elementary school every Monday at lunchtime, tutors were required to follow the procedure of escorting their student to their classroom as a transitioning and safety practice. Walking tutored students to their classrooms also helped the student-school bonding process, which Jones & Jones (2010, p. 44) refer to as one of eight important internal assets, commitment to learning, that is “associated with healthy personal development”. For the first four months of tutoring, once the school bell rang to mark the end of lunchtime recess, my student and I had experienced pleasant conversational dialogue during the walk to their classroom, which was on the second floor. Then, the student began walking so fast I was unable to keep up at my walking pace. After the following tutoring session, the student began running down the hallway and up the stairs, even though the student’s peers were entering the school in line formation at a calm walking pace. I gave considerable thought to what the best approach would be to change this behavior back to the calm, cooperative, respectful behavior the student exhibited for several months prior. The potentially harmful effects of my student’s extremely fast walking and running through the hallway and up two flights of stairs included tripping and hurting themselves and/or causing injury to others in the process. The actual immediate effect of the fast walking and running behavior is that the tutor is unable to fulfill the requirement of walking the student to their classroom.

Description of the Intervention

My proposed intervention involved four to five procedural steps. The first step was a dialogue between the student and I regarding the rules used at school, at the student’s home, and rules out in the community, and the reasons for those rules. The student was quite knowledgeable about rules that exist in all three areas as well as the reasons for those rules. I described and drew a mind map of a potential natural consequence that could result from not following a safety rule. The student would then draw mind maps of a natural consequence that would possibly happen if various safety rules were not followed in school, at home, and in the community. I used the instructional strategy of mind mapping because a mind map focuses on “only one main concept”, helps “the mind form associations almost instantaneously”, as well as enabling students to “order and structure their thinking through mentally mapping words or/and concepts” using images (SPS, 2009). In addition, this dialogue, which included telling the student how much I appreciated them for spending their lunchtime recess to practice and learn mathematics with such a positive happy attitude, served as the precursor for the second step in the intervention.

The second step of the intervention was showing the student a YouTube video about “Hallway Safety” created by high school students from Central Dauphin High School (CDHS, 2010). I put the video on pause at the end of the scene of a student running down the hallway and bumping into another student, knocking that student to the floor with all his books and papers scattering across the hallway. The intervention’s third step involved engaging the student in dialogue and reflection about that particular scene, as well as the use of mind maps to further the student’s associations with the safety concept of not running in the hallways or on the stairs.

The fourth step in the intervention was to make a verbal agreement that we would play a word game of the student’s choice while walking side by side at a calm pace together to their classroom after every subsequent tutoring session. We sealed our verbal agreement with a handshake. The fifth step of this intervention, if it became necessary, would be to formulate a written agreement that would be signed by both the student and I with an agreed upon consequence for any re-occurrence of the behavior.

My choice of intervention was supported by the social factors theory research of David Elkind, whose three basic contracts between adults and children is quoted in the Jones & Jones (2010, p. 39) text as “responsibility-freedom, achievement-support, and loyalty-commitment”. In my intervention I had “sensitively monitor[ed] the [student’s] level of intellectual, social, and emotional development in order to provide the appropriate freedoms and opportunities for the exercise of responsibility” through the use of the verbal contract (Jones & Jones, 2010, p. 39).

My intervention demonstrated the achievement-support contract as I expected age-appropriate behavior and achievements from the student while “providing the necessary personal and material support to help the [student] reach [the] expected goals” (Jones & Jones, 2010, p. 39). My use of the YouTube video and mind mapping exercise satisfied this achievement-support contract. Finally, my intervention fulfilled Elkind’s loyalty-commitment contract. This occurs through sharing with the student in a respectful and thoughtful manner appreciations for them coming to the library every Monday over the lunchtime recess. In addition, a verbalization of an appreciation for them putting in the effort to practice and learn mathematics was warranted. Then, it felt fairer to the student that they appreciated the time, effort, and energy the tutor puts into assisting them to increase their understanding of mathematics.

Evaluation of Mini-Intervention 1 Plan

The mini-intervention I planned and implemented for the third-grade student whom I was tutoring third grade mathematics went well. The student was very responsive to all phases of the intervention from my initial giving of appreciations for the student’s accomplishments and positive attitude through to our verbal agreement to play a word game of the student’s choice while walking at a calm pace together to their classroom after every tutoring session, sealing it with a handshake. What seemed to interest the student the most was watching the YouTube video entitled Hallway Safety, which was the collaborative effort of several high school students from Central Dauphin High School located in Harrisburg, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania in the United States (CDHS, 2010). The dialogue why rules exist was of less interest to the student based on the diminished enthusiasm they expressed facially (their broad smile relaxed to a grin) and observed body language (their upright, forward leaning posture relaxed). The drawing of mind maps, though initially a challenging task, became well appreciated by the student when they reviewed their finished product. Therefore, the use of mind mapping was a worthwhile positive experience and quite useful at encouraging the student’s critical-thinking and problem-solving skills.

Overall, the intervention had been successful according to the data I collected from April 18 until June 13 since the student had been exhibiting the appropriate expected behavior of staying on task during the tutoring and walking with me to their classroom at the end of the tutoring. In addition, as indicated by my comments on the several tutoring dates, the level of prompting reduced from a physical hand gesture plus verbal to no prompts/reminders at all.

In a way, the mini-intervention was a mini class meeting between two participants: the student and me. The benefits of holding regular class meetings with consistent formats is examined by Edwards & Mullis (2003, p. 20) who present research-based findings from numerous studies that assert classroom meetings “serve as an excellent vehicle for teaching” … ”students the academic, social, and emotional skills they must possess to function successfully at home, at school, and in the community”. Furthermore, according to this same article, “A substantial body of research implies that explicit instruction in social problem solving, especially those that teach empathy skills, averts subsequent problem behavior” Edwards & Mullis (2003, p. 20). Research also attests to class meetings helping students generalize conflict resolution instruction to real life situations because they are afforded practice of the necessary skills in a safe, controlled environment. Therefore, I was confident the mini-intervention I implemented provided the student with exactly these life skills lessons.

Upon closer examination, the mini-intervention generally followed the agenda structure outlined in the Edwards & Mullis article: I began with appreciations and compliments, followed by a peaceful conflict resolution and problem-solving activity using mind mapping and showing the YouTube video. Then, we practiced a little more problem-solving specific to the Hallway Safety video. However, the mini-intervention did not include what would be considered as old business or new business. Yet, the word game we played on the way back to the student’s classroom would be considered a “classroom encouragement activity”, according to Edwards & Mullis’ (2003, p. 23) description. Based on the positive outcome observed and recorded regarding the student’s appropriate expected behavior following the end of the morning’s mathematics tutoring session, I suggest educators use the Edwards & Mullis (2003) structure of a class meeting for all future teaching situations, both professionally and in their personal life.

References

Jones, V., & Jones, L. (2010). Comprehensive classroom management: Creating communities of support and solving problems (9th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Allyn & Bacon. ISBN: 9780205625482.

CDHS (2010). Central Dauphin High School Hallway Safety, uploaded on Feb 5, 2010. Retrieved on April 10, 2011, from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ue0TElhHy0Y

Edwards, D., & Mullis, F. (2003). Classroom Meetings: Encouraging a Climate of Cooperation. Professional School Counseling, 7(1), 20-28. Retrieved from EBSCOhost .

SPS (2009). Instructional Strategies Online. Saskatoon Public Schools. Retrieved on April 23, 2011 from http://olc.spsd.sk.ca/de/pd/instr/strats/mindmap/index.html

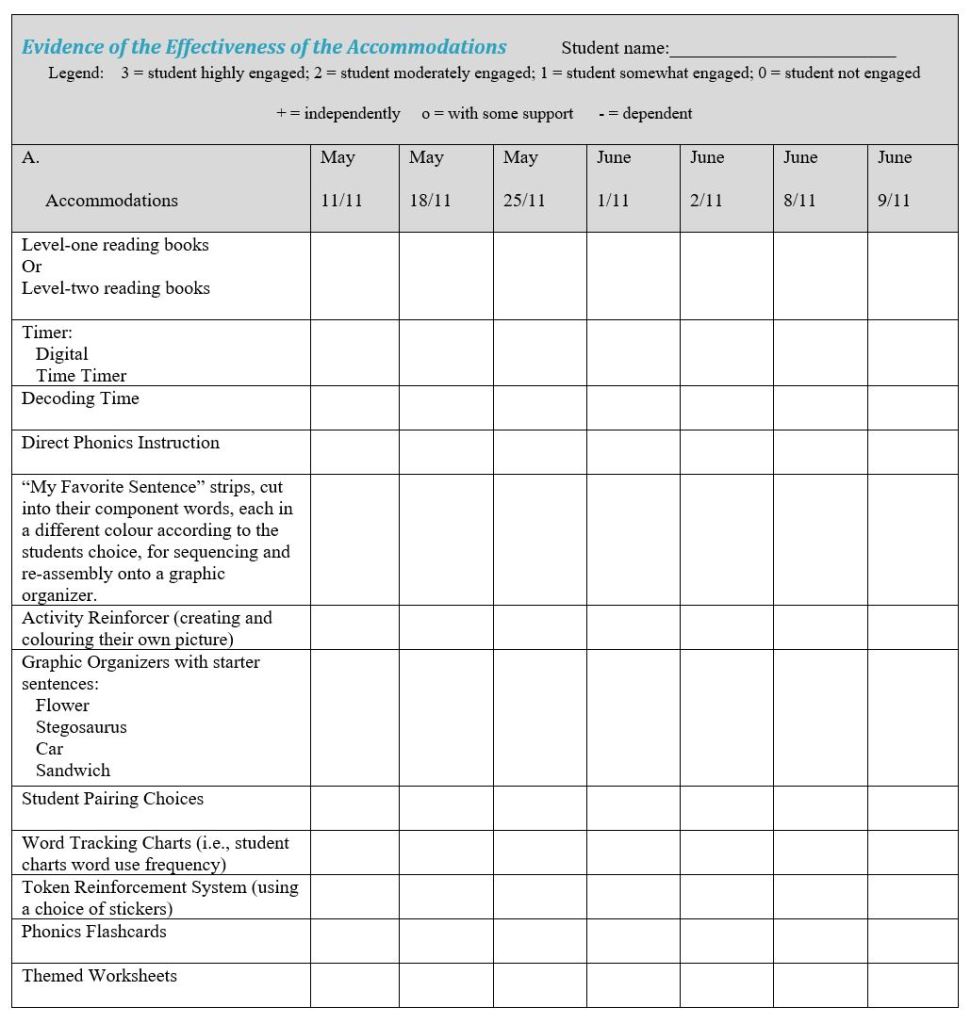

Mini-Intervention 2: Tracking Accommodations

Introduction

In 2011, I began a new in-school tutoring position at another Peel Board elementary school. Once per week I was tutoring nine kindergarten students acknowledged by their classroom teachers and special education teacher as low achieving readers. The area designated for the tutoring was outside the doorway to the classroom at a child-sized desk for a period of fifteen to twenty minutes per student. None of the children had a formal identification and IEP. However, these kindergarten students’ classroom teacher and the school’s Special Education/ESL support teacher requested the extra assistance to bolster these children’s reading level. The use of level 1 and 2 reading books that the school possessed, tracking the words a student had difficulty pronouncing, and the sentence they choose to print to describe the theme of the book they read comprised the data the Special Education/ESL teacher requested I collect during each tutoring session. Accommodations other than these, I have added to the Accommodation Chart below, in which I have used pseudonyms in place of the students’ names.

Assessment of How Accommodations are Meeting Student Needs

On the first day of my new in-school tutoring venue, their teacher introduced me to all the students in the classroom. I called for the first of nine students to come read to me out in the hallway where the child-sized desk and chair awaited. The school’s Special Education/ESL support teacher provided me with nine level-one reader books, an accommodation in and of itself. The books were of various interest topics.

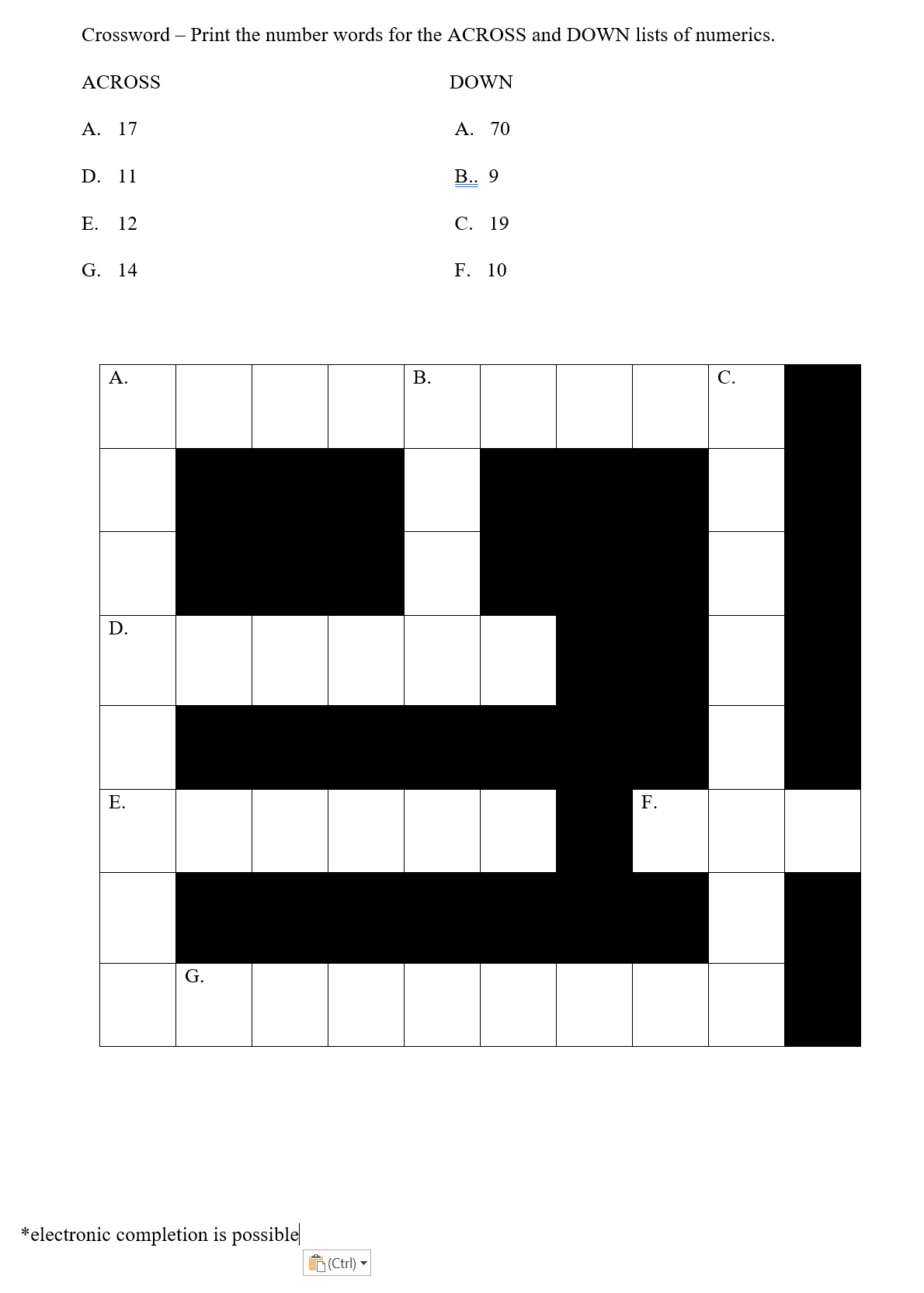

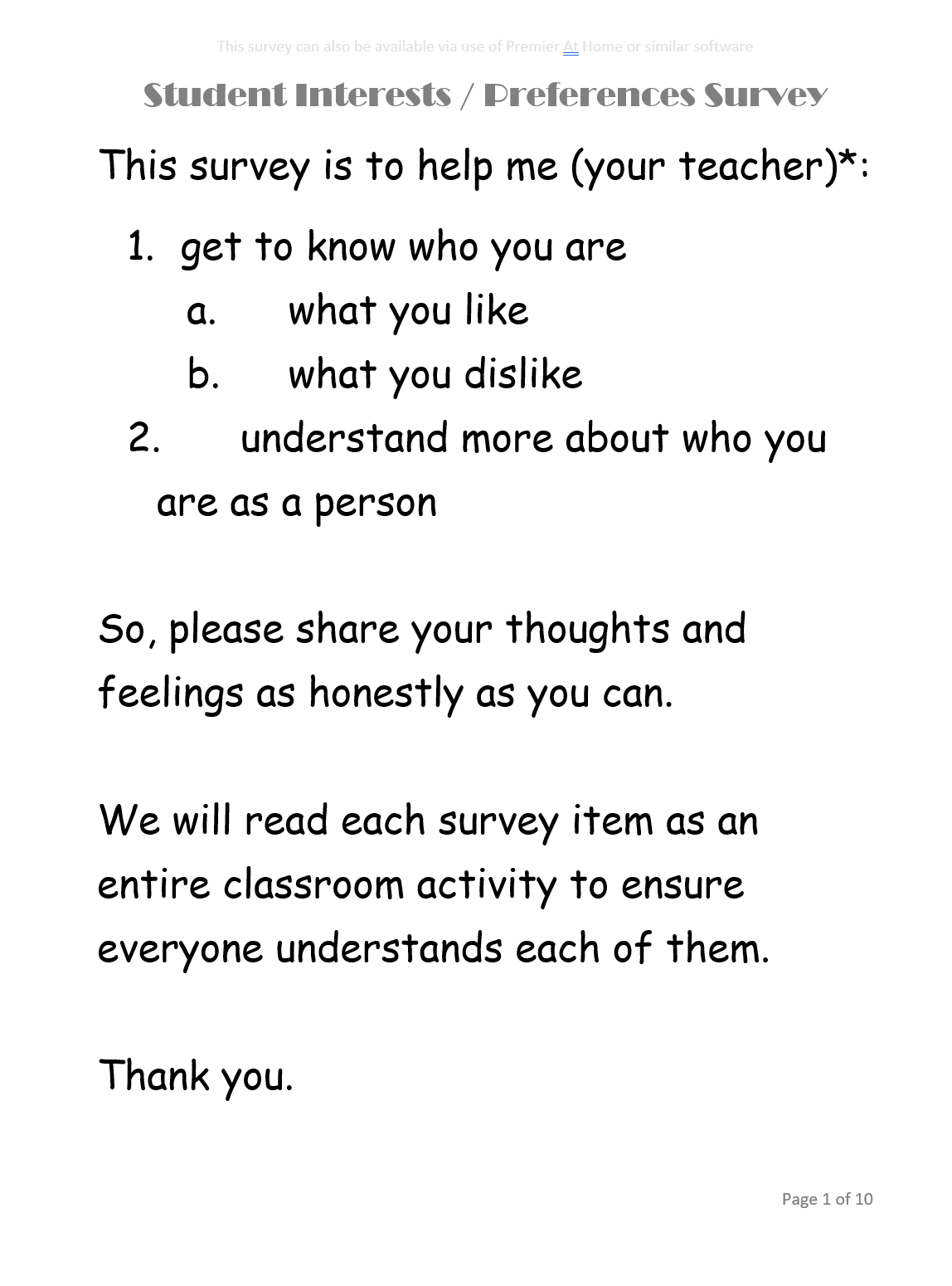

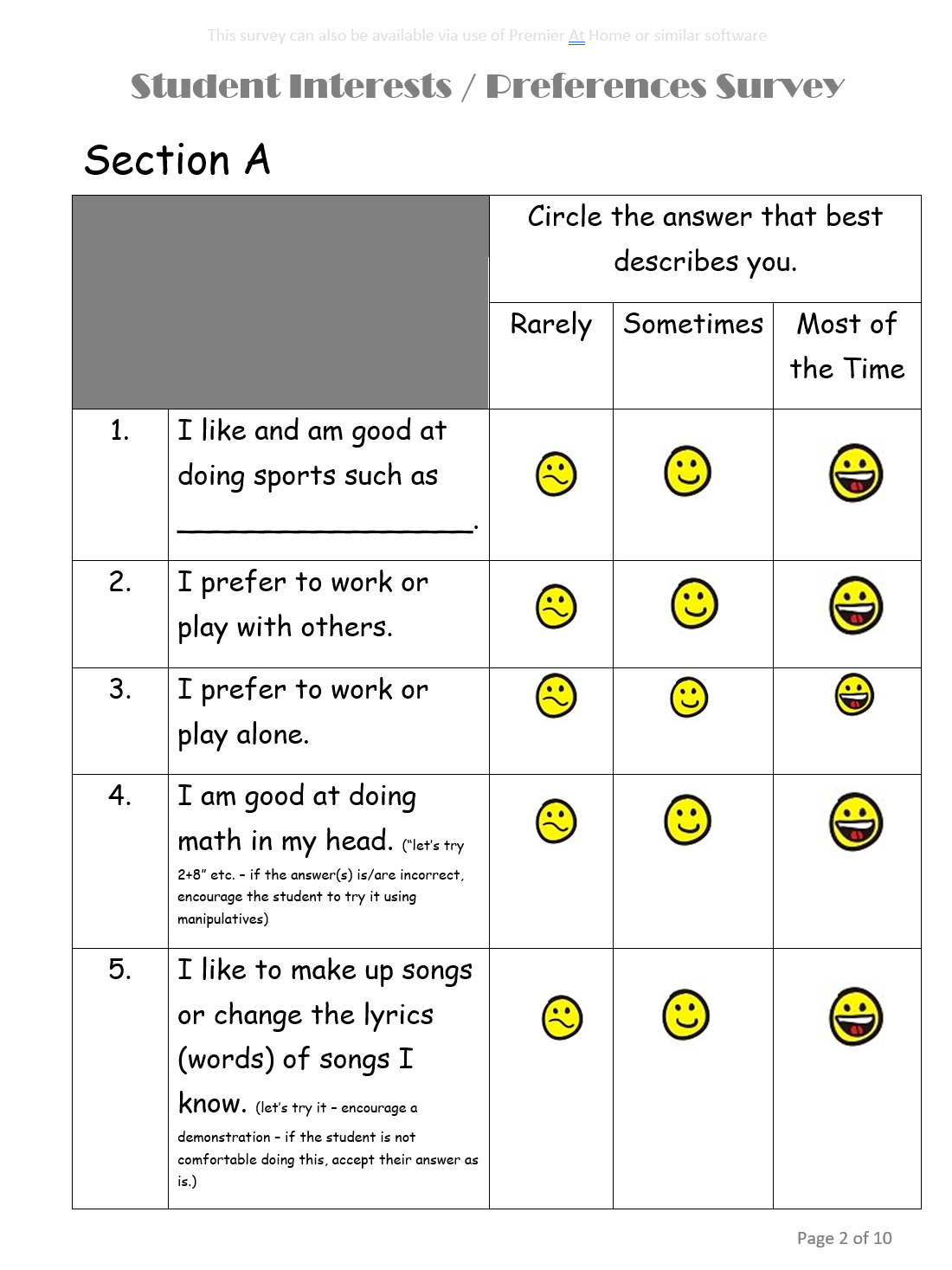

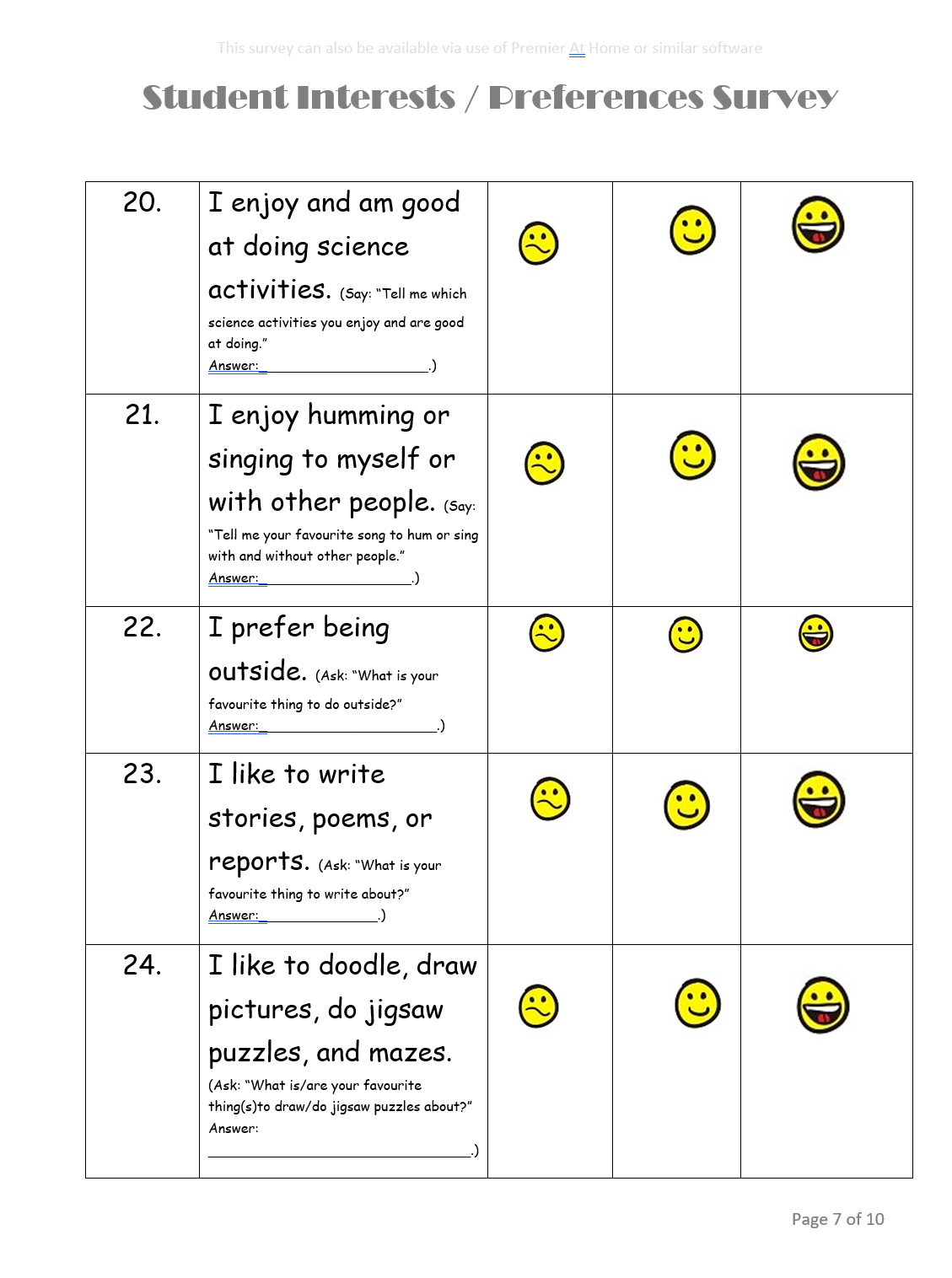

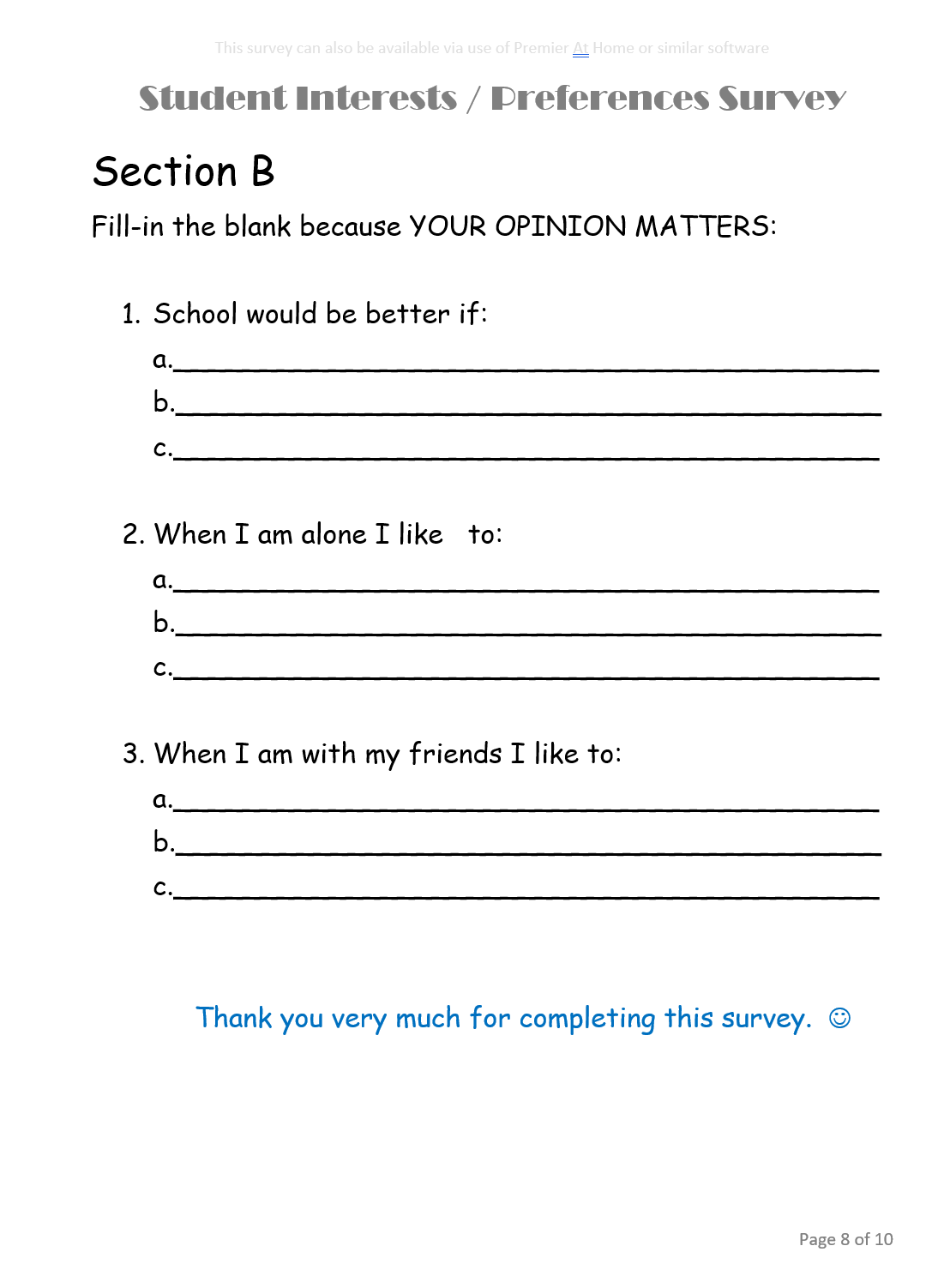

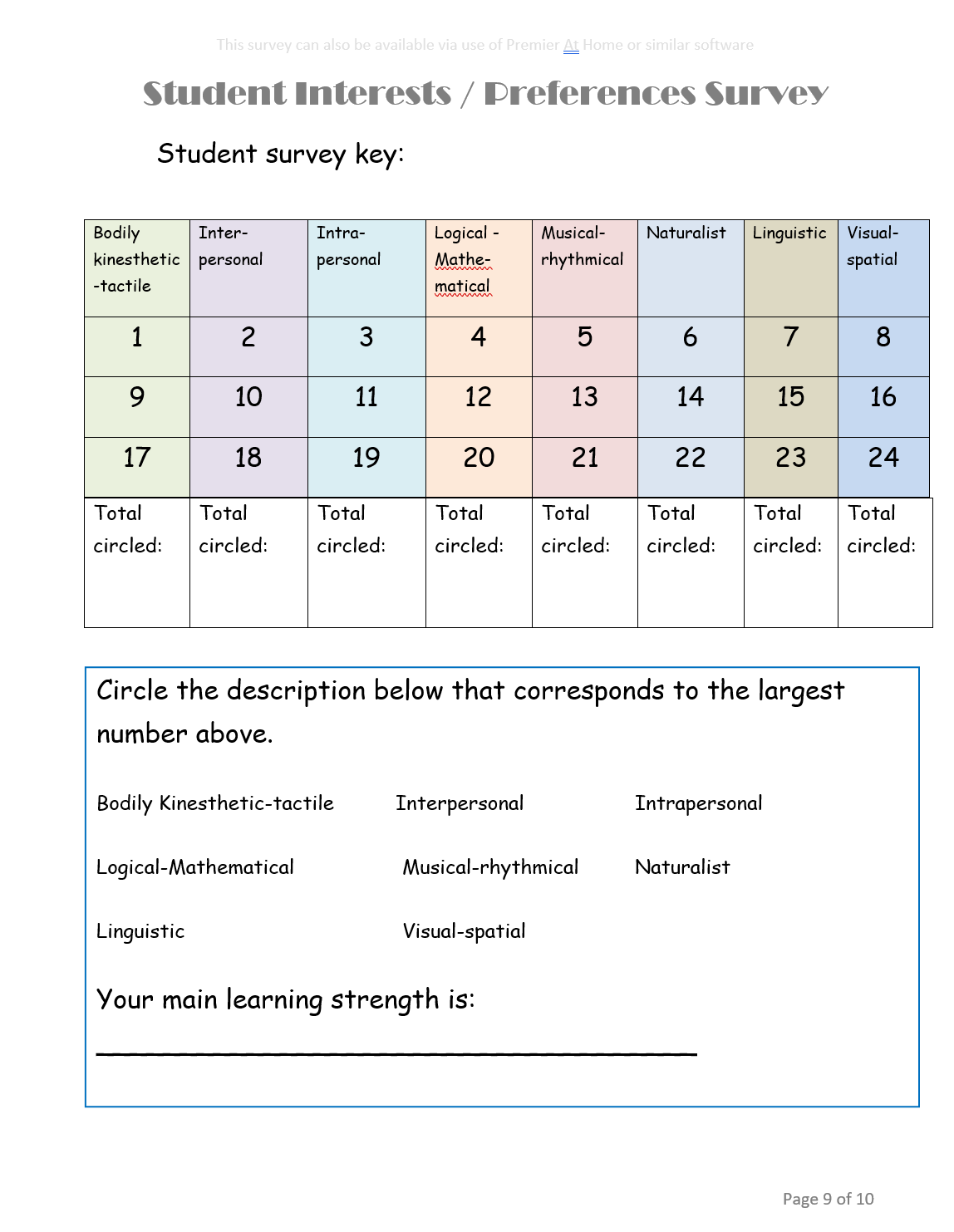

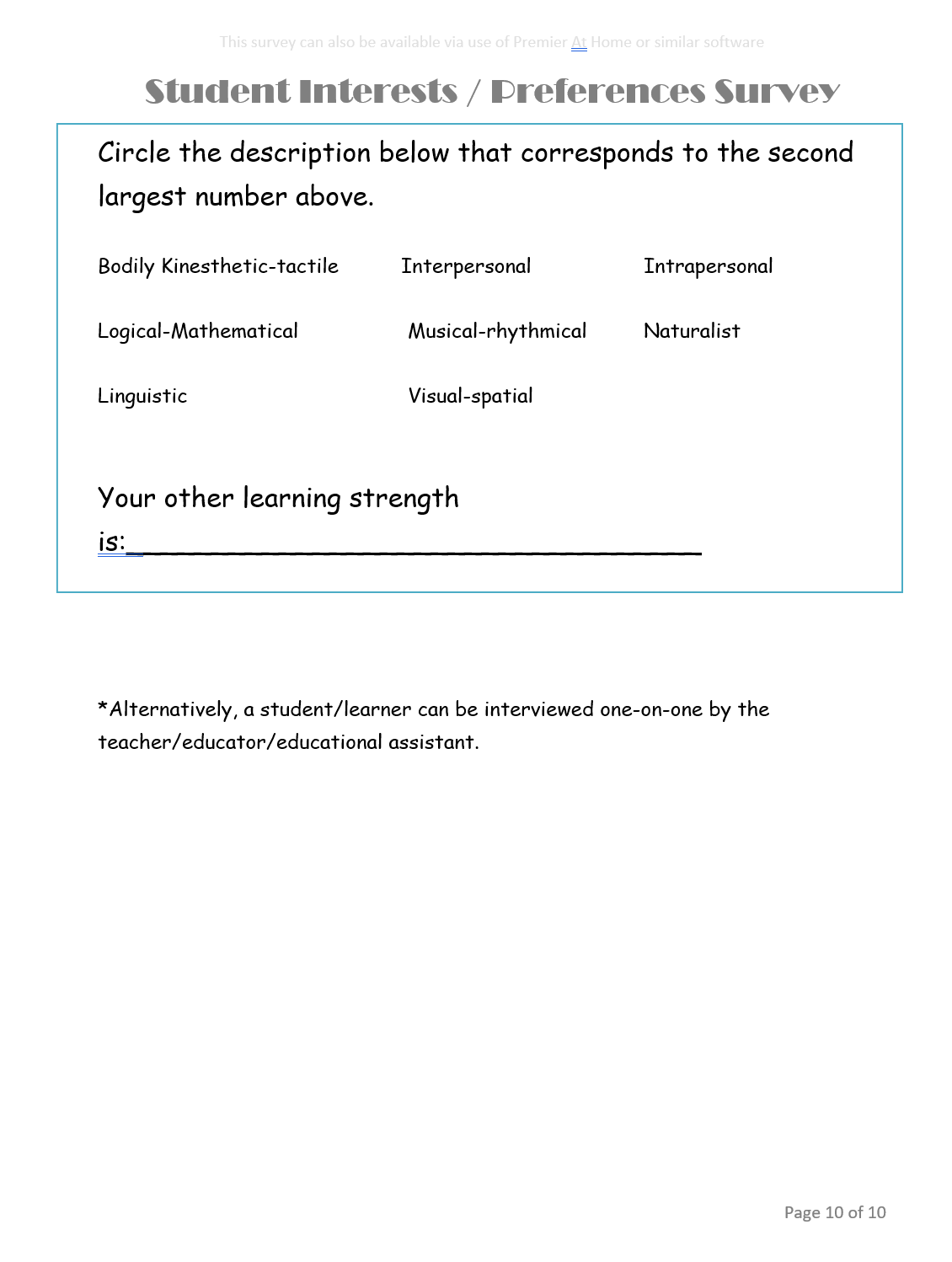

Before I invited a child to select a book of their choice to read aloud to me, I told them I wanted to get to know them better by finding out what they like and don’t like. I asked for their response to twenty-four queries, where the responses could be either most of the time, sometimes, or rarely, each paired with an image of a broadly smiling face, a grinning face, and a displeased face, respectively. Each query corresponded to one of eight multiple-intelligences (Gardner, 1999). For example: Do you like and enjoy doing sports? relates to the Bodily-Kinaesthetic intelligence; Do you prefer to work with others? relates to the Interpersonal intelligence; Do you prefer to work relates to the Intrapersonal intelligence; Do you enjoy playing games of strategy like checkers or cards? relates to the Logical-Mathematical intelligence; Do you like watching and playing with animals? relates to the Naturalist intelligence; Do you like to hum or sing to yourself or with other people? relates to the Musical-Rhythmical intelligence; Do you enjoy writing stories, poems, or reports? relates to the Verbal-Linguistic intelligence; and, Do you enjoy doodling, drawing pictures, doing jigsaw puzzles, and mazes? relates to the Visual-Spatial intelligence. This provided me with greater understanding about the types of accommodations that would best suit each student. For example, Gazelle has strong visual-spatial and bodily-kinaesthetic intelligence that can be paired with their secondary intelligence, logical-mathematical, by inviting her to explore and chart how many times a particular word is used within the story she had read. Each time the student found the word they were looking for they would colour a square in the chart and say the word. This would help the student to transfer word recognition, word meaning, and pronunciation from short to long-term memory by engaging her in an activity that both interested and challenged her (Gardner, 1999; Jones & Jones, 2010). Tiger is another student who benefited from using the word-tracking chart as they also had a strong logical-mathematical intelligence as determined by their responses to the multiple-intelligences survey.

The digital timer worked well giving the students a clear indication of how much time was left in the session. I would continue to provide the students with a choice of using either the digital timer or a time timer, the latter being a stronger visual support for those children who do not prefer the logical-mathematical intelligence as a learning modality.

The variety of level-one books was acceptable for the first in-school tutoring session as each student was able to select a book without hesitation that interested them. However, I requested that a greater variety of level-one books be made available for future in-school tutoring sessions to ensure the students have books of high interest to read. In addition to the level-one books, decoding time is set at thirty seconds to allow for a student’s processing of a word’s structure, and at least an attempt at pronouncing the word to the best of their ability.

The use of direct teaching phonics to each student when they came upon a word they did not know how to pronounce worked well as did the use of printing each syllable component in different colours that the student was allowed to select, modelling pronunciation, and having them practice saying the word aloud until fluent. In addition, the creation of sentence strips based on two sentences, one I chose and one the student chose from the book, in which each word is printed in a different colour (where the students selected the colours used), including sentences cut into their word parts for sequencing, and then re-assembled, worked well. This activity was of interest to every student and challenging to some. I would continue to implement this accommodation and extend it once the students started to create their sentences that described what the story was about using the graphic organizers I created.

The activity reinforcer that worked well with the students was allowing them to draw a picture of their choice using legal sized white paper and washable primary colour markers. They all enjoyed doing this. One student gave me her picture, and another promptly folded it, with some help from me, and put it into their knapsack to take home to their father.

The use of graphic organizers in a variety of shapes such as a car, sandwich, flower, or stegosaurus, which included starter sentences, served to help the students to organize their thoughts into well-structured, semantically correct sentences. Jones & Jones (2010, p. 232) state, “Many students simply need assistance and training in how to organize material, so it is more readily accessible for retention or creative use”.

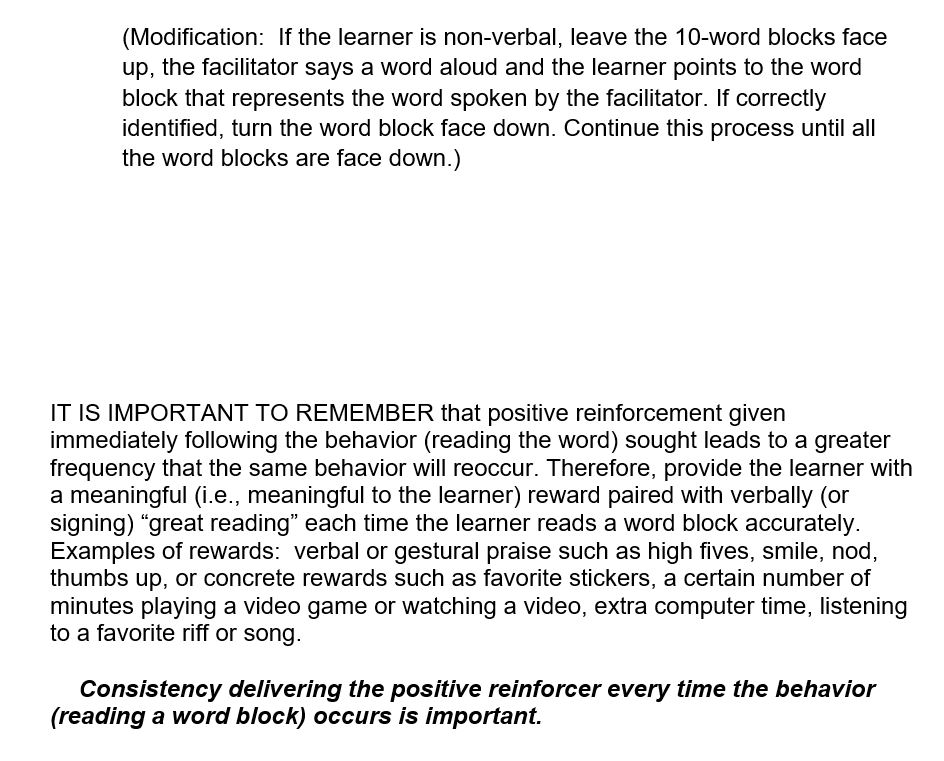

Furthermore, I put into effect other accommodations that built interpersonal and intrapersonal skills. I provided the choice of pairing with another student with similar interests, teaching them how they can help each other become better readers, make connections to their own lives, use self-reflective thought to define their opinion about the story they read, and communicate that opinion with clarity to the other and to me. Jones & Jones (2010, p. 247 to 248) state, “Provid[ing] opportunities for students to select whether they will work alone, in pairs or with a small group” is a way of “adjusting environmental factors to meet students’ learning needs”. Another accommodation I implemented was a token reinforcement system using a variety of stickers that appealed to each student. According to Jones & Jones (2010, p. 402), “Token reinforcement refers to a system in which students receive immediate reinforcement in the form of a check, ship, or other tangible item that can be traded in for reinforcement at a future time”. I would use a token board on which each student will place a mark of their choice (check, an X, a dot, a circle, etc.) once they have finished reading a page aloud a level-one book fluently. With each in-school tutoring session, reading fluency (i.e., the skill to read text quickly and accurately) support in the form of modeling the phonetic pronunciation of a word, was faded. The fading of support increased the skill necessary to earn the mark on the token board or the number of marks that must be earned overall, which depended on each student’s reading fluency level as some progressed faster than others.

Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the Accommodations

My plan for evaluating the effectiveness of the accommodations included measuring and evaluating the effects of the implementation through the use of a grading system where a high level of engagement (referred to as being in flow) would equate to a level 3; a moderate level of student engagement would equate to a level 2; a low level of student engagement would equate to a level 1; and non-engagement would equate to a zero. Villa & Thousand (2003, p. 67) describe “flow as the state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter; the experience itself is so enjoyable that people will do it even at great cost, for the sheer sake of doing it”, and identify “the experience of flow” as evidence of “intrinsic motivation”. An accommodation that does not achieve a level 3 engagement for an individual student could be modified or removed and replaced with another accommodation that may serve to promote higher engagement.

In addition to tracking the effectiveness of the accommodations, I included measures in the plan that would provide evidence of how the implementation made a difference. The data/evidence collected included the reading level of the book students choose; each book’s title; the words each student had difficulty decoding; anecdotal notes about each student’s reading style (i.e., pointing and reading one word at a time vs. chunking/scanning visually several words together); and sentence sequencing and re-assembly from the student’s own description of what the story is about (comprehension). A student’s increase in reading fluency such that the original list of mispronounced or unpronounced words reduces in size and is extinguished altogether for six level-one books, and the comprehension sentence clearly described what the story was about served as the evidence that the implementation of the accommodations was effective. Operationally a student was asked to demonstrate comprehension by either inferring meaning from the book they read or providing explicit responses to formative oral questions. The following charts entitled, Evidence of the Effectiveness of the Accommodations chart, (A) Accommodations and (B) Student Achievement outline the planned evaluation of effectiveness for the accommodations.

The Actual Effectiveness of the Implementation of the Accommodations

According to the data collected over the course of seven days, spread over five weeks, most of the accommodations proved to be quite successful as the students were able to read the same books again without mispronunciations or decoding difficulties. After three weeks, the students happily read more books of their choice with more confidence than when we began the reading recovery intervention on May 11th. What I would do differently is ask the classroom teacher about which students pair well together and which do not. This is because on two different occasions, with two pairs of students, off-task behaviors began increasing slightly because the learners were more interested in socializing with each other than on achieving the learning goal of helping each other improve their reading.

References

Gardner, H. (1999). Intelligence Reframed, Multiple Intelligences for the 21st Century, Basic Books.

Jones, V., & Jones, L. (2010). Comprehensive classroom management: Creating communities of support and solving problems (9th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Allyn & Bacon. ISBN: 9780205625482.

Villa, R. A., & Thousand, J. S. (2005). Creating an inclusive school. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. ISBN: 9781416600497.

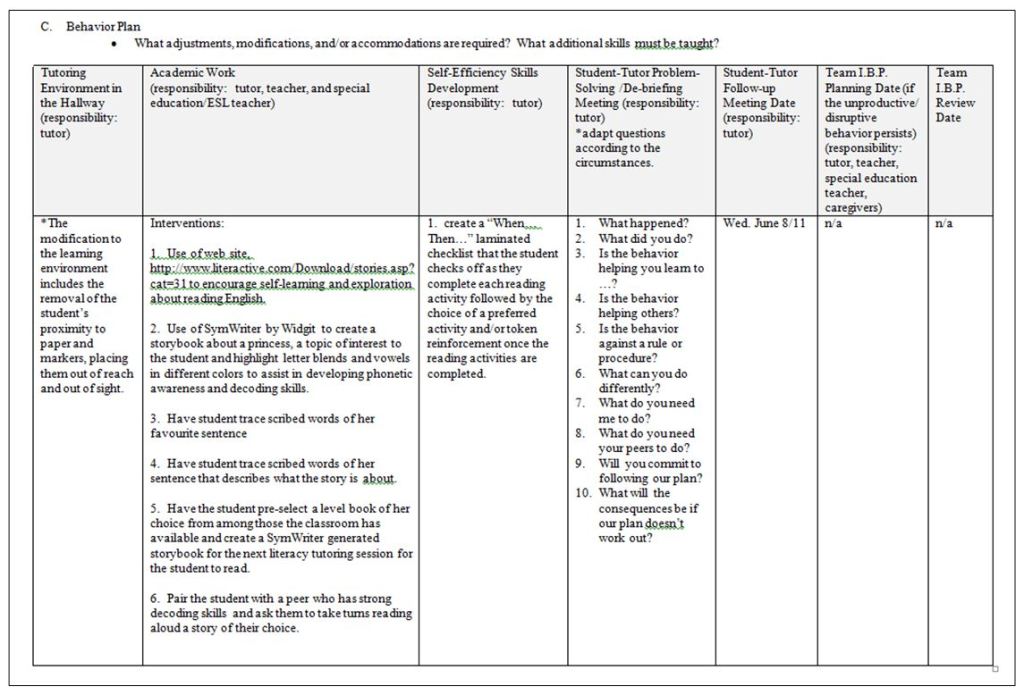

Mini-Intervention 3: Functional Behavioral Assessment

Assessment of How Well I Am Meeting the Needs of This Student

I had been diligent and consistent at implementing the mini-intervention 2 accommodations including: The use of Level 1and 2 reader books of various interest themes; the use of a Time Timer; the provision of more time for decoding; direct instruction of phonics; the opportunity for the students to create sentence strips and cut them into their word parts for sequencing and re-assembly onto a reading activities sheet; as well as activity and token reinforcers in the way of drawing a picture and/or selecting a sticker of their choice once the reading activities were completed. However, as Jones & Jones (2010, p. 362 – 363) attest, “students occasionally need highly structured programs to help them change specific behaviors” that “require some form of individualized intervention”…”to help them function responsibly and successfully within even the best classroom and school environment”. It is for this reason that I considered the instructional strategies I used as well as the content, tutoring environment (which was in the hallway just outside the classroom’s doorway), and the student-teacher, student-peer relationship factors. Using a functional behavior analysis of students’ behavior, I assessed the reason for their behavior is primarily the avoidance of the activity of reading as some students, according to their kindergarten teacher and special education teacher, entered kindergarten with no decoding skill development. I carefully and thoughtfully examined “the interventions [I had] already made to modify the learning environment and provide the student with special assistance in meeting the multiple demands” of the literacy tutoring session (Jones & Jones, 2010, p. 369).

The students enjoyed the social interaction of the read aloud and the supporting comprehension activities. Their social inclination was the reason that pairing with a peer during read alouds and supporting comprehension activities was implemented on a continuous and consistent basis. One student gladly selected a level 1 or 2 book, then, rather than attempting to sound out the words in the sentences, looked at the pictures associated with the words on the page opposite and created their own sentence to describe the picture’s content. In spite of phonics direct instruction, this strategy did not help this student, as they did not retain the knowledge of the sounds associated with the letters and their blends. Hence, the idea of introducing this student to an interactive literacy web site in which animated level books were paired with animated visual representation of phonetic pronunciation of each word as the student clicked on each word in a sentence. I also decided to try re-creating level books of the student’s choice using SymWriter by Widgit. SymWriter produces words with symbol representation images above the words to assist the learner’s comprehension of the words. SymWriter’s manufacturer, Widgit (2011), describes the software as, “a symbol-supported word processor that any writer, regardless of literacy levels, can use to author documents. Writers of any age or ability can use the Widgit Symbols to see the meaning of words as they type, supporting access to new or challenging vocabulary”. I also used various colored pencils to highlight letter blends and vowels to increase the student’s awareness of phonetics and therefore increase their decoding skills.

Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the Behavior Plan Accommodations

Using the Functional Behaviour Assessment Data Collection Chart, I tracked the occurrences of unproductive off-task behavior of the student subject once the accommodations, adaptations, and modifications were implemented.

In order to control for the possibility of a time of morning effect, I ensured the student was called to participate in the literacy tutoring at 10:40 a.m., just in time for the 10:45 a.m. time slot. The effectiveness of these new strategies would be apparent if the number of behaviors diminishes or were extinguished over time, which would be assessed when the number of unproductive off-task occurrences on June 15/11 was subtracted from the number of occurrences collected as baseline data on May 25/11. The larger the number, the greater the reduction in unproductive off-task behaviors, therefore, the interventions implemented would be considered successful. In addition, my plan for evaluating the effectiveness of the new accommodations, adaptations, and modifications for the subject student included measuring and evaluating the effects of the implementation using a grading system to track the level of engagement as well as the student’s level of independence during read alouds and supplemental comprehension activities. Similar to the mini-intervention 2, a high level of engagement (referred to as being in flow) would equate to a level 3; a moderate level of student engagement would equate to a level 2; a low level of student engagement would equate to a level 1; and non-engagement would equate to a zero. Villa & Thousand (2003, p. 67) describe “flow as the state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter; the experience itself is so enjoyable that people will do it even at great cost, for the sheer sake of doing it”, and identify “the experience of flow” as evidence of “intrinsic motivation”. An accommodation that does not achieve a level 3 engagement for an individual student would be modified or removed and replaced with another accommodation that may prove to be more effective at promoting a higher level of engagement. Tracking the student’s level of independence would be tracked by using a “+” sign to indicate total independence during the activity, “o” to represent some guided support such as phonetic decoding modeling for some words and direct assistance with sentence structures and word formation. A “-“represented complete dependence during all aspects of the literacy activities.

Furthermore, just as in the mini-intervention 2, I continued to track the effectiveness of the accommodations, adaptations, and modifications by providing evidence of how the implementation was making a difference. The data/evidence collected continued to include the reading level of the book the student chose; each book’s title; the words the student had difficulty decoding; anecdotal notes about the student’s reading style (i.e., pointing and reading one word at a time vs. chunking/scanning several words together); and sentence sequencing and re-assembly from the student’s own description of what the story was about (comprehension). The students’ increase in reading fluency would be apparent when the original list of mispronounced or unpronounced words reduced in size and was extinguished altogether for six level-one or level-two books. In addition, the students’ comprehension sentences, when done independently, describing what the story was about served as evidence that the implementation of the accommodations was effective. Operationally the student was asked to demonstrate comprehension by either inferring meaning from the book they read or providing explicit responses to formative oral questions. The following charts entitled, Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the Accommodations, Adaptations, and/or Modifications chart, (A) Accommodations, Adaptations, and/or Modifications on the top of page 70, and (B) Student Achievement, outline the planned evaluation of effectiveness for the original and new accommodations, adaptations, and modifications.

Assessment and Evaluation of the Behavior Plan’s Effectiveness